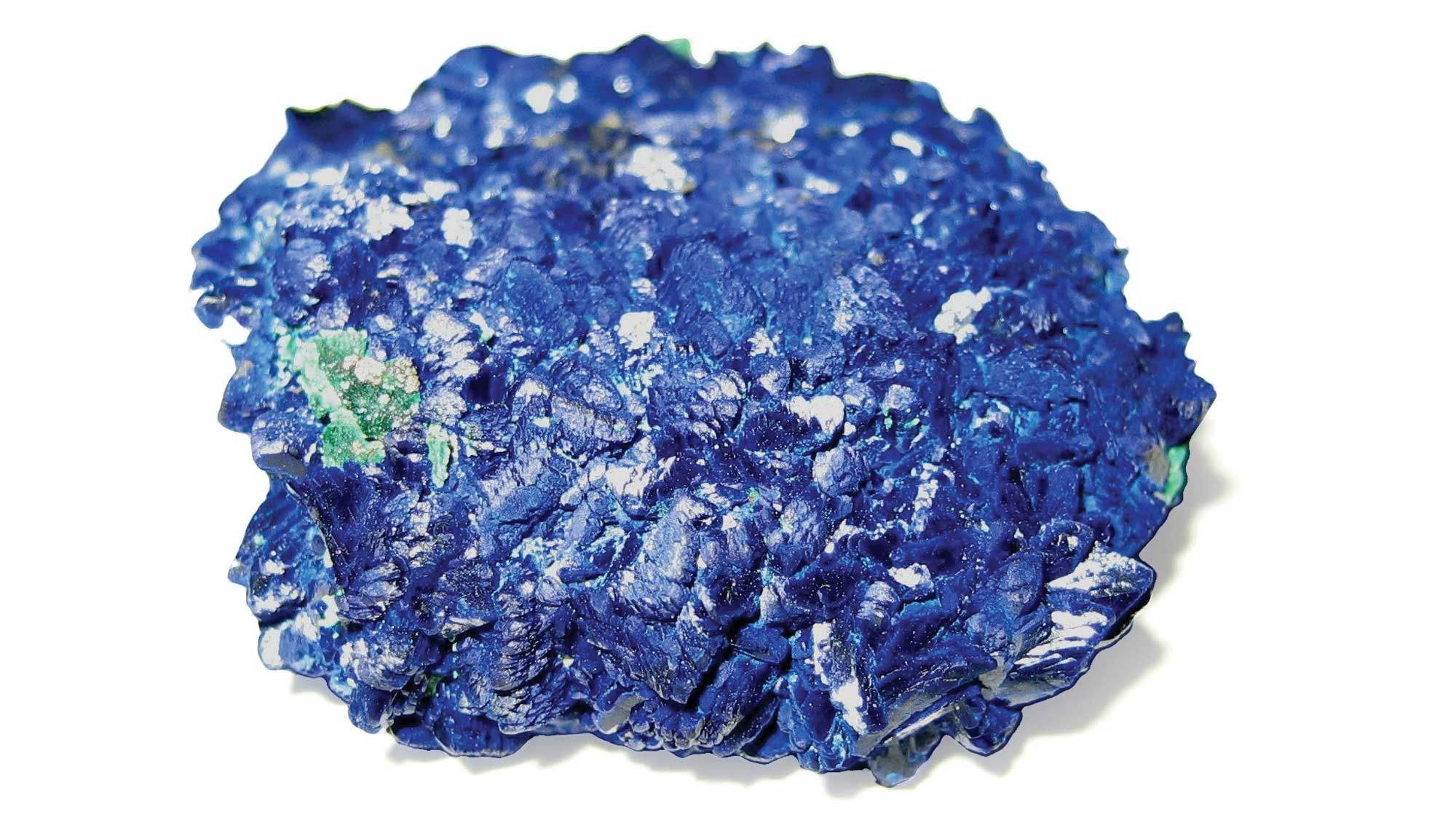

Azurite is the basic copper carbonate mineral found in many parts of the world in the upper oxidized portions of copper ore deposits. Azurite mineral is usually associated in nature with malachite, the green basic copper carbonate that is far more abundant. Azurite is generally described as a bright blue or sometimes as a greenish-blue. Azurite varies in masstone color from deep blue to pale blue with a greenish undertone depending on such factors as the purity of the mineral and the grade (particle size) of the pigment. Azurite was the most important blue pigment in European painting throughout the middle ages and Renaissance.

Origin and History of Use

The name “azurite” comes from Latin, borrowed a Persian word (lazhward) for blue, which in the form of aquarium became azurium, and gave us our word azure.

Occasional use of azurite as a paint pigment began with the Egyptians. According to some authorities, azurite was found in paint pigment as early as the Fourth Dynasty in Egypt. However, the pigment was not commonly used until the Middle Ages, when the manufacture of the ancient synthetic pigment Egyptian blue was forgotten. Produced artificially as blue bice or blue verditer since the seventeenth century, azurite was replaced when Prussian blue was discovered in the eighteenth century.

Azurite was often used in tempera paintings of the Middle Ages when ultramarine (lazurite) was not available or considered too expensive. However, it has been observed to darken in egg tempera when applied to the upper layers of the painting.

Lippo di Dalmasio (1353?–1410), The Madonna of Humility, c. 1390, egg tempera on canvas, 110 × 88.2 cm, National Gallery, London

Lippo di Dalmasio painted several images of the Virgin of Humility, so-called because she is shown sitting on the ground. Scientific analysis has revealed that the Virgin’s cloak is painted with azurite. The bright blue of azurite would have contrasted strongly against the gold background, but as it is sometimes prone to darkening over time, it now appears almost black.

When oil paint dominated European art, azurite continued to be used, especially since it was much less expensive than ultramarine. In Northern Europe painting, it was often used in underlayers of paintings to strengthen the weak tinting strength of ultramarine.

Dirk Bouts, The Virgin and Child, 1400?–1475, c. 1465, oil with egg tempera on oak, 37.1 × 27.6 cm (10.8 × 14.6 in), National Gallery, London

The warm, glowing colors in this painting by Dirk Bouts are characteristic of applying layers of transparent oil glazes over an opaque underpainting. Like many early Netherlandish painters, Bouts used cheaper pigments for the underlayers. Here, for example, the Virgin’s robe is painted with azurite beneath the more expensive ultramarine.

Italian, Florentine, An Allegory, c. 1500, tempera and oil on wood, 92.1 x 172.7 cm, National Gallery, London

In the nineteenth century, a painting of Venus with three putti was thought to be by Sandro Botticelli. The National Gallery in London acquired it with Botticelli’s famous Venus and Mars. The attribution of the painting, now laconically entitled An Allegory, has been downgraded, but this does not call into question its authenticity. The binding medium has been confirmed as egg tempera, typical of the period. The blue pigment of the sky is composed of azurite mixed with lead white, while the dark green grass of the background contains spherulitic malachite.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis (EDX) analysis of these green particles identified mostly malachite with a small chlorine impurity. Such results are consistent with the investigations of spherical malachite from other fifteenth-century Italian paintings in the National Gallery of London, where in all instances, the pigment was found to be associated with silica and potassium aluminum silicate.

Titian fully exploited a wide range of pigments available to him, including the much-prized ultramarine, azurite, and red lake from kermes.

Raphael, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, c. 1503–1505, oil and gold on wood, 172.4 cm × 172.4 cm (67.9 in × 67.9 in), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This important early altarpiece by Raphael was painted for the small Franciscan convent of Saint Antonio in Perugia and hung in a part of the church reserved for nuns. Raphael often used azurite in his work. The azurite blue of the Virgin’s mantle has darkened due to its degradation into green malachite. Now, this mantle looks greenish.

The use of azurite declined sharply in the seventeenth century when artificial copper carbonate pigments, known as blue bice and blue verditer, were invented. These pigments later fell in use after the invention of Prussian blue in 1704.

Source

Azurite is a secondary mineral that usually forms when carbon dioxide-laden waters descend into the Earth and react with subsurface copper ores. The carbonic acid of these waters dissolves small amounts of copper from the ore. The dissolved copper is transported with water until it reaches a new geochemical environment. This new environment could be where water chemistry, temperature changes, or evaporation occurs. If conditions are right, the mineral azurite might form. A significant accumulation of azurite might develop if these conditions persist for a long time. This has occurred in many parts of the world.

Azurite precipitation occurs in subsurface rock’s pore spaces, fractures, and cavities. The resulting azurite is usually massive or nodular. In rare situations, azurite is found as stalactitic and botryoidal growths. Well-formed monoclinic crystals are infrequently found. These can only occur if azurite precipitates unrestricted in a fracture or cavity and is not disrupted by later crystallization of rock movements.

Azurite is found in many parts of the world in the upper oxidized portions of copper ore deposits and malachite. Azurite from Natural Pigments is from copper ore deposits from several locations: Dzhezkgazgan, Kazakhstan, Congo, and Hubei province, China.

Permanence and Compatibility

Despite azurite being a carbonate and hence sensitive to acids, it has a good record with respect to permanence when employed in oil and tempera media. However, it is darkened when exposed to sulfur fumes, primarily where it is used in mural paintings. It is unaffected by light. Azurite pigment is said to turn green due to alteration to malachite. The transformation of blue azurite to a green compound has frequently been observed in wall paintings. An often-quoted example is the color change in the cycle of the legend of Saint Francis in the Upper Church of Saint Francis at Assisi. The alteration is thought to be due to the presence of alkali and high moisture conditions.

Alteration and subsequent darkening of azurite have been observed, most frequently in wall paintings. Chlorine-rich alteration products have been identified, which products include paratacamite and atacamite.

In studies by the National Gallery, most of the samples of azurite were unaffected by exposure to light, including samples bound in linseed oil, acrylic, casein, and glue. Despite many references in the literature to changes in azurite, only two samples showed any alteration in these experiments: a sample in watercolor and a mixture of azurite and sodium chloride in a glue medium [Saunders].

Although copper pigments tend to exert both a siccative and antioxidant effect in an oil medium, some examples have shown that azurite tends to discolor when applied in thick, coarse-textured layers.

Oil Absorption and Grinding

No data has been published on the oil absorption properties of azurite. Coarsely ground azurite produces a dark blue pigment; fine grinding produces a lighter tone. We offer a fine and medium ground pigment with an intense blue hue. Because of its refraction index, Azurite is most successfully employed in aqueous mediums, such as tempera.

Toxicity

Azurite is moderately toxic, and care should be used in handling the dry powder pigment and the pigment dispersed in a medium. For more information on handling pigments, please visit How to Safely Handle Art Materials and Pigments.

References

Being Botticelli. National Gallery website. Last accessed on July 2, 2022: Link.

Dunkerton, J. and Spring, M., with contributions from Billinge, R., Kalinina, K., Morrison, R., Macaro, G., Peggie, D. and Roy, A.. ‘Titian’s Painting Technique to c.1540’. National Gallery Technical Bulletin 34, 2013. 4–31. Last accessed on July 2, 2022: Link.

Gettens, R.J. and FitzHugh, E. West. ‘Azurite and Blue Verditer’. Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2, ed. A. Roy, Washington/Oxford 1993. 23–35; see 27.

Saunders, D., Kirby, J. ‘The Effect of Relative Humidity on Artists’ Pigments.’National Gallery Technical Bulletin 25. 62–72. Last accessed on July 2,022: Link.

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names: | English: azurite French: azurite German: Azurit Italian: azzurrite Spanish: azurita |

||||||

| Synonyms: | English: blue verditer, bice, Mountain blue French: bleu de montagne, bleu d'Allemagne German: Bergblau Italian: azzurro della magna Latin: lapis armenius, azurium citramarinum |

||||||

| Nomenclature: |

|

||||||

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Blue |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural Inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Blue 30 (PB30) |

| Chemical Name: | Copper Carbonate |

| Chemical Formula: | Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2 |

| CAS No.: | 1319-45-5 |

| Series No.: | 7 |

| ASTM Lightfastness | |

| Acrylic: | Not Listed |

| Oil: | Not Listed |

| Watercolor: | Not Listed |

| Physical Properties | |

| Particle Size (mean): | 25 microns |

| Density: | 3.80 g/cm3 |

| Hardness: | 3.50–4.00 |

| Refractive Index: | 1.758 |

| Oil Absorption: | 25 grams oil / 100 grams pigment |

| Health and Safety | This natural substance has not been evaluated for acute or chronic health hazards. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic risks of this and other chemical products by keeping them out of your body. Copper carbonate is classified as hazardous under OSHA regulations (29CFR 1910.1200) (Hazcom 2012): Acute toxicity—Oral—Category 4 Skin irritant—Category 2 Eye irritation—Category 2A Based on this information, we present the following health warning: WARNING! Contains Copper Carbonate. Harmful if swallowed. Causes skin irritation. Causes severe eye irritation. Avoid ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhalation of dust. Conforms to ASTM D-4236. |

For a detailed explanation of the terms in the table above, please visit Composition and Permanence.