What is Resin? Gum? Balsam?

When used in its most specific sense, the word “resin” is a hydrocarbon secretion of many plants, particularly coniferous trees. The resin produced by these plants is a viscous liquid composed mainly of volatile terpenes. Oleoresins are naturally occurring mixtures of oil and resin. Other resinous products in their natural condition are a mixture of gum or mucilaginous substances known as “gum resins.” Mastic gum is an excellent example of a gum resin.

Balsam is an exudate from various plants. Balsam (from Latin balsamum “gum of the balsam tree,” ultimately from Semitic, Aramaic busma, Arabic balsam, and Hebrew basam, which means “spice,” “perfume”) owes its name to the biblical Balm of Gilead. Some authors consider true balsams to be oleoresins containing benzoic acid or cinnamic acid, and their esters obtained from the exudates of various trees and shrubs. Hence, all balsams are “oleoresins” or, less precisely, “resins,” but not all resins are balsams. Interestingly, Canada balsam, larch balsam, and copaiba balsam are terpenes containing the characteristic resin in solution and are not regarded as true balsams.

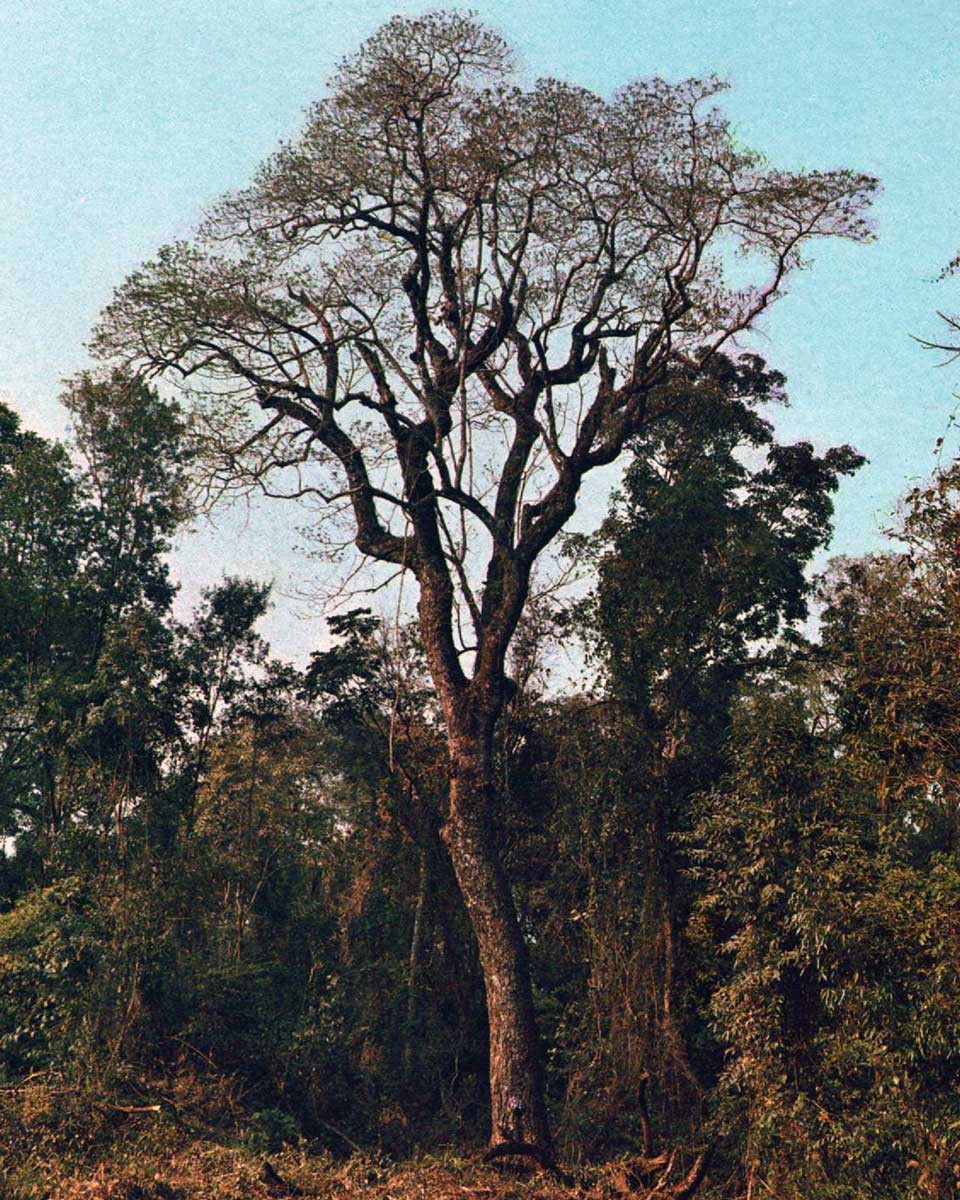

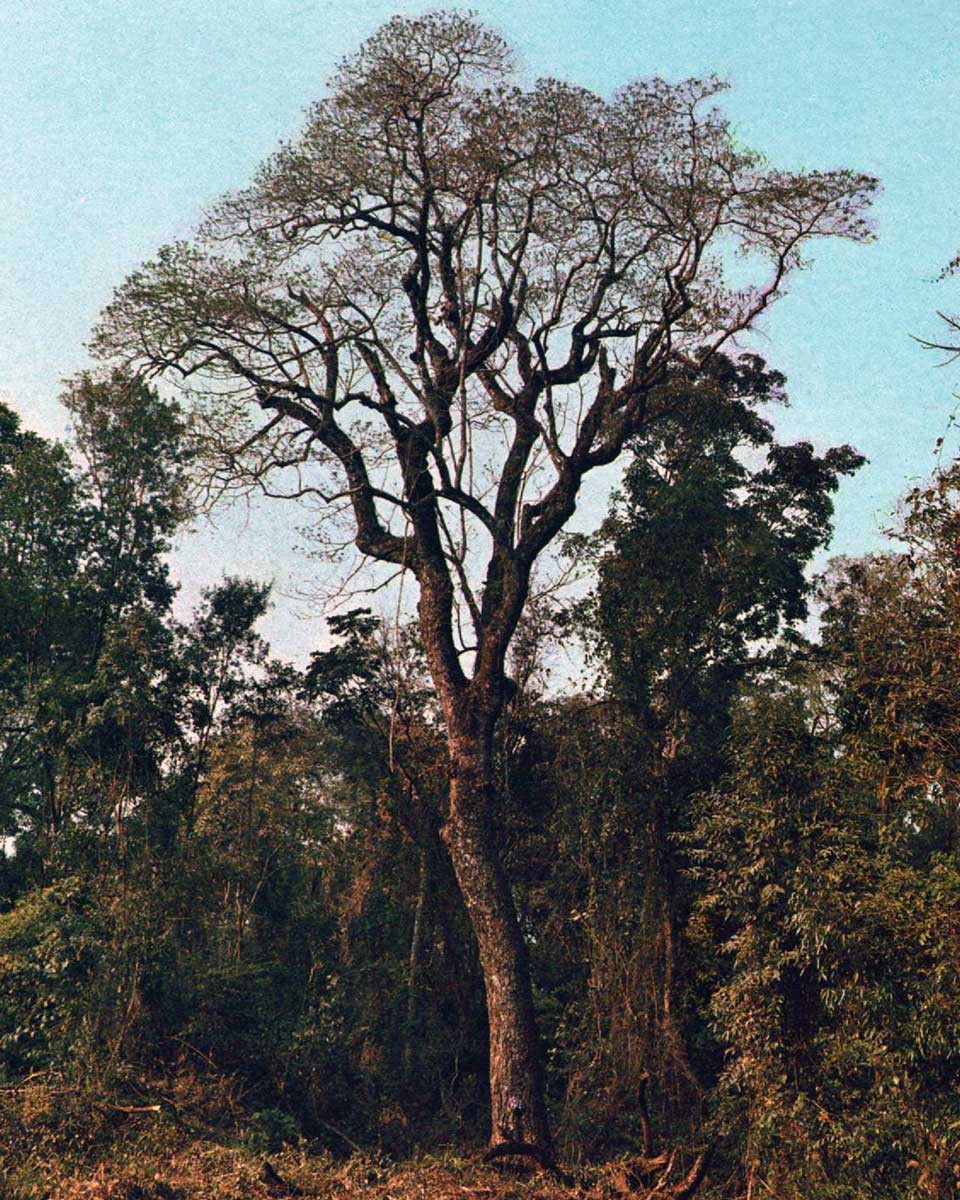

Balsam of Tolu or Balsamum tolutanum from Myroxylon balsamum

Myroxylon, the source of Balsam of Peru and Balsam of Tolu, is a genus of trees grown in Central America and South America. Pictured here is Myroxylon peruiferum.

In chemistry, a balsam is a solution of plant resins in plant-derived solvents or essential oils. Such mixtures can include resin acids, esters, or alcohols. Balsam is a fluid to highly viscous liquid and often contains resin particles. Over time the balsam loses its solvent components or converts into a solid material by autoxidation.

Mastic

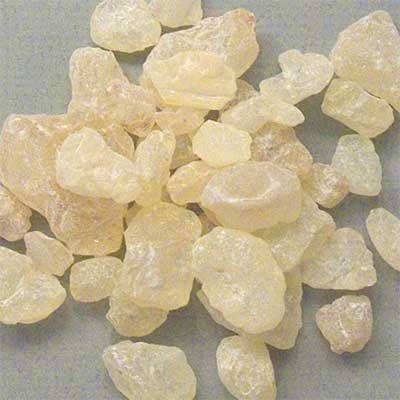

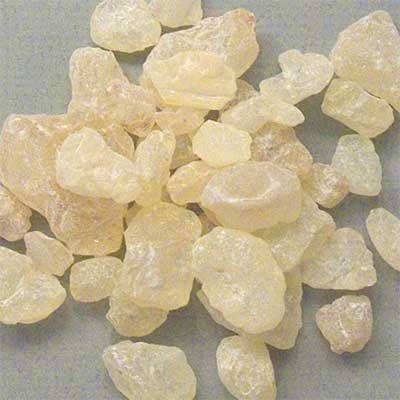

Mastic is a resin obtained from the mastic tree or bush (Pistacia lentiscus). It is also known as tears of Chios, being traditionally produced on the island Chios, and, like other natural resins, is produced in "tears" or droplets. Mastic is excreted by the resin glands of Pistacia lentiscus and dries into brittle, translucent resin pieces. When chewed, the resin softens and becomes a bright white and opaque gum. The flavor is bitter at first, but after some chewing, it releases a refreshing flavor similar to pine and cedar.

Masitc resin often form in the shape of tears as they drip from the Mastic bush.

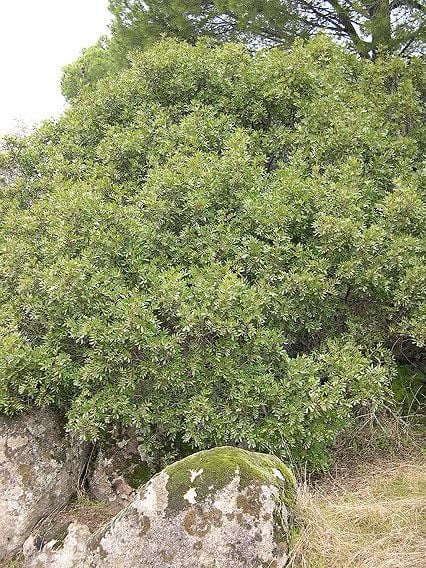

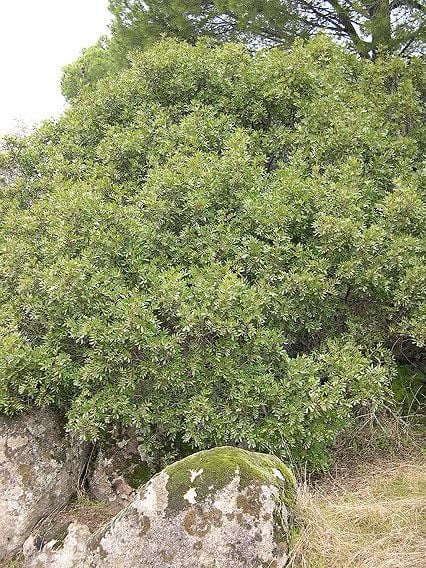

Mastic bush (Pistacia lentiscus)

Dammar

Dammar, also called dammar gum or damar gum, is a resin obtained from the tree family Dipterocarpaceae in India and Southeast Asia, principally those of the genera Shorea or Hopea (synonym Balanocarpus). The resin of some species of Canarium may also be called dammar. Most are produced by tapping trees; however, some are collected in a semi-fossilized form on the ground. The gum varies in color from clear to pale yellow, while the fossilized form is grey-brown. Dammar gum is a triterpenoid resin containing many triterpenes and their oxidation products. Many are low molecular weight compounds (dammarane, dammarenolic acid, oleanane, oleanonic acid, etc.), but dammar also contains a polymeric fraction composed of polycadinene. The name dammar is a Malay word meaning ‘resin’ or ‘torch made from resin.’

Dammar resin dissolved in turpentine to make dammar varnish was introduced as a picture varnish in 1826. It was later commonly used in oil painting, both during the painting process and after the painting is finished. Dammar varnish and similar gum varnishes auto-oxidize and yellow over a relatively short time. This effect is more pronounced on paintings stored in darkness than with works on display in light due to the bleaching effects of light on oil colors.

Batik is made from dammar crystals dissolved in molten wax to prevent the wax from cracking when it is drawn onto silk or rayon. Modern encaustic paints are made with dammar resin added to beeswax, to which pigment is then added. The dammar resins increase the melting point of the beeswax and, thereby, the hardness of the encaustic paint.

Larch Turpentine

Larch turpentine or sometimes referred to as “larch balsam,” is the exudate of the Larix europaea (European Larch). It is used as a plasticizing resin for spirit and oil varnishes

Venice Turpentine

Venice turpentine is a product of the European Larch or other closely-related larch species. When pure, it is limpid, with a yellow color, sometimes with a green tint, tenacious, thick like molasses. It can be heated with other resins and combined with linseed oil and turpentine to make an oil varnish. It requires exposure to the air for many years before it becomes hard and brittle. Hence it is used only as a plasticizing resin in varnishes and mediums.

Venice turpentine is often mixed with gum rosin and turpentine spirits to make it less expensive. The product sold under the name of Venice turpentine (especially in tack shops) is often factitious, consisting entirely of gum rosin (colophony) and turpentine. Some tests can identify adulteration of Venice turpentine with rosin, and we have used them on several brands of Venice turpentine sold in tack shops.

Just to let you know how confusing and contradictory the terminology for these materials can be, Gettens and Stout (Rutherford Gettens, George Stout. Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopedia [New York: D. Van Nostrand & Co., 1942]) identify Venice turpentine as a balsam, but Frederic Hyde, PaB. (Solvents, Oils, Gums, Waxes and Allied Substances [London: Constable & Company, Ltd., 1913]) lists it as a solvent. (He also writes that it is “closely related to Canada balsam.") It is both a resin and solvent because it contains both mixed.

I do not recommend Venice turpentine in oil painting because it usually contains rosin, which oxidizes and darkens upon exposure to the atmosphere. Pure larch oleoresin would be preferable, but only as a plasticizer in the medium. Most natural resins are susceptible to darkening and embrittlement and should be used sparingly in a painting.