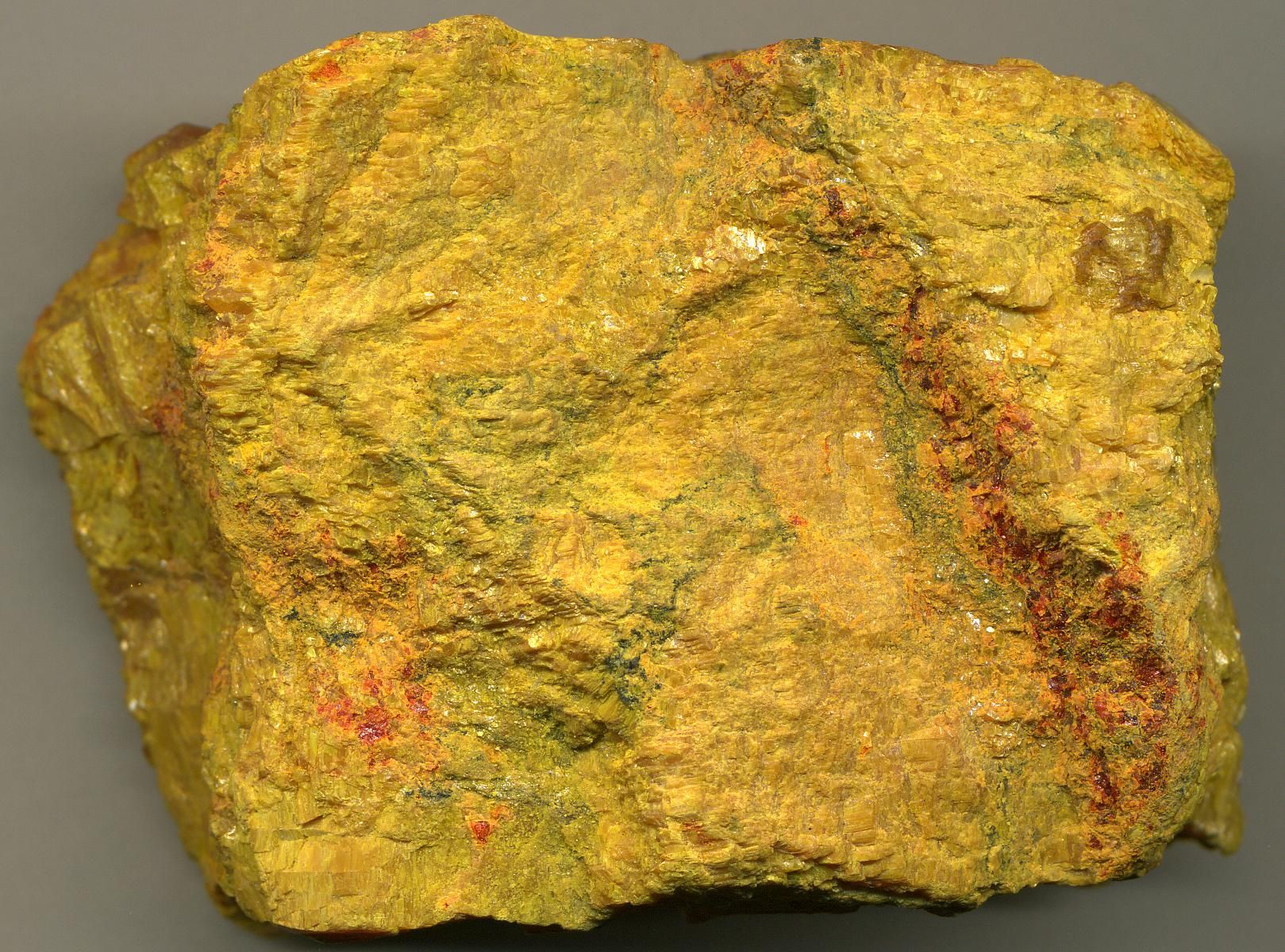

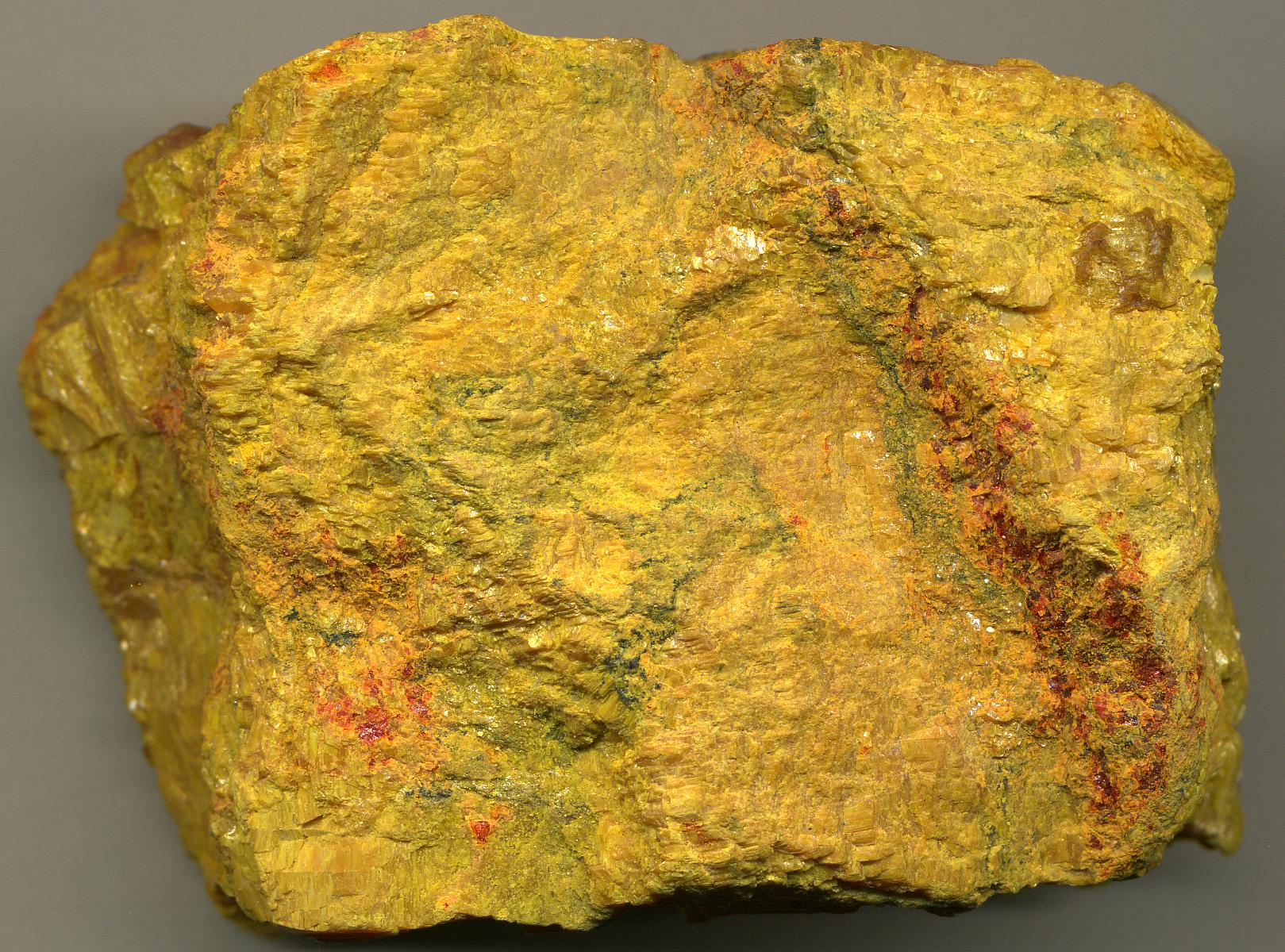

Orpiment is a rich lemon or canary yellow with fair covering power and good chemical stability as a pigment. It is designated as brilliant yellow in Munsell notation 4.4Y 8.7/8.9. It is an arsenic sulfide mineral that occurs naturally in small deposits as a product of hydrothermal veins, hot spring deposits, and volcanic sublimation, although nowadays, it can be easily obtained artificially. The arsenic content makes it toxic, although it was also used in medicine, cosmetics, and as a biocide in ancient times.

Orpiment and realgar from deposits near Manhattan, Nevada, USA

History and Use of Orpiment

Orpiment has been known since ancient times. Aristotle’s student, Theophrastus, and Roman writers Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius mention it in their writings. Theophrastus calls the mineral arrenikos, and is related to the Persian zarnikh, which is based on the word zar, the Persian for gold. A similar name, arsenikos, was later used by Dioscorides. In Greek, the term would correspond to “strong” or “manly.” It may have been so named because elemental arsenic was used in small amounts to treat blood and nerve ailments. Some thought this mineral contained gold, perhaps because arsenic is sometimes found in gold deposits. Orpiment is derived from the Latin auripigmentum, or “golden pigment.” That is why Agricola called the mineral operment derived from the English and French names orpiment, Italian orpimento, and Spanish oropimento. We could interpret the meaning of the name in two ways: as a mineral with a color similar to gold or as a mineral to which the gold pigment gives color.

Alchemists Believed They Could Make Gold with Orpiment

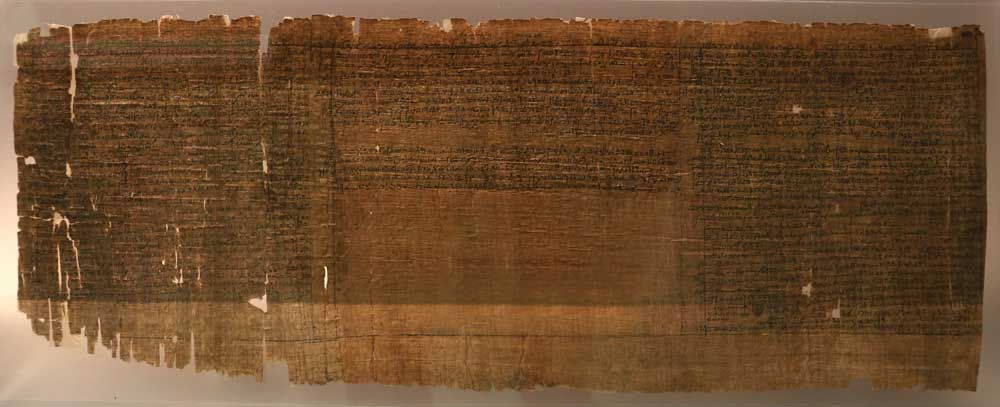

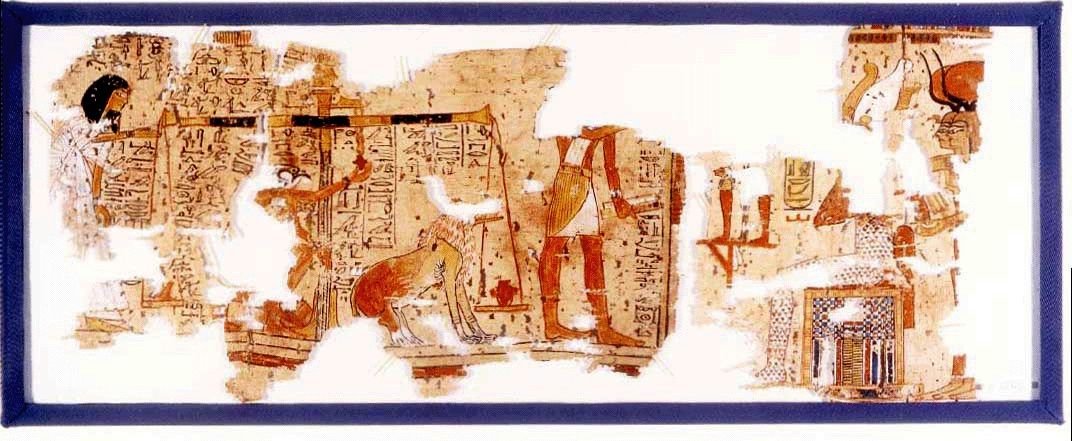

The Hellenistic Leyden papyrus described its use for late Egyptian painting, as does the Mappae Clavicula for early medieval painting. The pigment has been described in various other medieval manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.

The Leyden papyrus, written in Egypt about 1,700 years ago and found among the wrappings of a mummy in the early nineteenth century, includes dozens of metallurgical recipes.

Alchemists believed metals were compounds produced underground through the combination of simpler substances.

This idea dates back to Aristotle’s belief that metals grew in the earth. This process was thought to be associated with color changes like plants change color as they ripen. Impure metals in the ground were supposed to turn into gold over centuries.

By combining these substances in just the proper ratios, alchemists believed, they could turn base metals into gold.

Orpiment was an ideal candidate to produce gold because it looked like gold, and alchemists believed it was, in fact, a substance that was on its way to maturing into gold.

Use in Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, orpiment was a starting material used to prepare various arsenic compounds used to destroy insects, weeds, and tan leather. In medicine, it was used to treat syphilis, malaria, and lung gangrene. In the military industry, it is used to prepare munitions. If it is crushed into powder and mixed with a paint binder oil, a beautiful yellow painting color is obtained. The bust of the ancient Egyptian queen Nefertiti was partially painted with it [Nefertiti].

The paints on Nefertiti’s bust are in keeping with the well-known spectrum of ancient Egyptian natural pigments, including red ochre, yellow orpiment, and carbon black, as well as the artificially produced Egyptian blue and green frit (Egyptian green), applied in a variety of shades, to create the queen’s skin tone.

Nefertiti Bust, Egypt, Tell el-Amarna, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1351–1334 BC, 49 × 24.5 × 35 cm; material: limestone, painted stucco, quartz, wax, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlun

Closely related to, although not as widespread as orpiment, is an orange pigment called realgar (the orange arsenic disulfide natural mineral, AS2S2), which can often be found in the same deposits. Despite its toxicity, it was the only orange pigment until chrome yellows and oranges were introduced at the beginning of the nineteenth century. An interesting feature of realgar is that prolonged light exposure turns it into a yellow compound called pararealgar without changing its elemental composition.

Papyrus, 13th century BC, Petrie Museum, University College London. The following pigments were detected in this original papyrus thanks to a Raman spectroscopy analysis, orpiment (yellow), pararealgar (yellow form degraded realgar), and carbon (carbon).

Orpiment in Venetian Renaissance Paintings

Orpiment was used in Venetian paintings where a bright yellow was required, especially those of Tintoretto. Orpiment seems to have had little known use in Northern Europe, where lead-tin yellow appears to have been one of the dominant yellows in a European palette.

Tintoretto’s palette was augmented with orpiment, and realgar, which remained firm favorites of Tintoretto throughout his career. Their occurrence has been found in Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne. Rare in European easel painting in general, they are common in sixteenth-century Venetian painting from Giorgione onwards [Plesters].

Tintoretto (1519–1594), Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet, 1548–1549, oil on canvas, 210 × 533 cm (82.6 in × 17.4 ft), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Orpiment was identified in the upper layer of the orange-yellow robe of Saint Peter (whose feet Christ is washing). Realgar was identified in the lower layer of the same orange-yellow drapery.

Titian, The Holy Family with a Shepherd, 1510, oil on canvas, 99.1 × 139.1 cm (39 × 54.7 in), National Gallery, London

Orange paint passages based on a combination of realgar and orpiment have been said to be typical of Venetian paintings of this period—and are indeed seen quite regularly in works by Veronese and Tintoretto. Titian did not use them to the same extent, especially in his later works. In The Holy Family with a Shepherd of about 1510, Joseph wears an intensely orange cloak painted with red and yellow earth but with orpiment and realgar in the lighter areas [Dunkerton].

Titian, The Money Tribute, 1516, oil on panel, 75 × 56 cm (30 × 22 in), Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Orpiment appears in Titian’s later paintings, such as The Tribute Money, in the brightest highlights on the Pharisee’s tunic, which is more yellow than orange, combined with a brownish-yellow earth pigment.

Jan Gossaert, A Man with a Rosary, c. 1525–30, oil on oak panel, 69 × 49.1 cm, National Gallery, London

While it was not unusual to find orpiment in Venetian paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it does not often appear in pictures of Northern Europe. Jan Gossaert, a French-speaking artist in the Low Lands, used it in A Man with a Rosary. The yellow pigment is seen in the man’s ring, and the green cord of the rosary does not appear to be lead-tin yellow, which is typical for yellow in Netherlandish paintings. Unusually, its appearance in the stereomicroscope appears to be orpiment [Campbell].

Twin Creeks Mine, Nevada, USA, is an open-pit gold mine, owned and operated by Nevada Gold Mines LLC, a source of gold and also orpiment and realgar minerals.

Sources of Orpiment

Orpiment is a rare mineral that usually forms with realgar. In fact, the two minerals are almost always together. Crystals of orpiment are extremely rare as it usually forms masses and crusts. The masses are sometimes transparent to a degree and have a gemmy quality. The yellow color is unique to orpiment and can be confused only with a few other minerals. The largest quantities of orpiment were found in Turkish Kurdistan (Julamerk) and the republic of Georgia. The orpiment in Italian painting often came from the fumaroles of Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei in Tuscany. Since the later Middle Ages, the pigment was also artificially made. This pigment would most likely result from the sublimation of arsenic, arsenic oxide, and orpiment with and without the addition of sulfur. Notable occurrences of orpiment are found today in Kyrgyzstan; Romania; Peru; Japan; Utah, USA; and Australia.

The streak of a mineral is the color of the powder produced when it is dragged across a surface. Unlike the apparent color of a mineral, the streak of finely ground powder generally has a more characteristic color, such as the trail of color produced from the orpiment stone.

Permanence and Compatibility

Early authorities usually described orpiment as fading readily, or at least to some degree on exposure to light. It is said to be incompatible with lead- or copper-containing pigments. Molart studied the mechanisms of deterioration in orpiment [van Loon]. Several medieval painting guides do not recommend mixing orpiment with lead white, red lead, or verdigris. However, it must also be noted that it has been identified in paintings mixed with indigo, red iron oxide, azurite, Prussian blue, green bice (artificial malachite), and smalt. It cannot be applied to wet plaster and hence is not recommended in buon fresco painting techniques.

Rublev Colours Orpiment pigment.

Oil Absorption and Grinding

No data has been published on the oil absorption properties of orpiment. It isn't easy to grind because of its micaceous structure. For this reason, it is often relatively coarse. Adding ground glass to the pigment has been suggested to facilitate grinding and dispersion in linseed oil.

Toxicity

The toxicity of arsenic sulfide pigments has been known for years. Extreme caution must be used when handling the dry orpiment pigment and in any soluble form to avoid inhaling the dust or ingesting it.

References

The Bust of Nefertiti. Last accessed on July 2, 20022: Link

Campbell, Lorne. ‘Jean Gossart, A Man with a Rosary’ published online 2011, from ‘The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings with French Paintings before 1600’, London. Last accessed on July 2, 2022: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/research/jan-gossaert-a-man-with-a-rosary

Dunkerton, J. and Spring, M., with contributions from R. Billinge, H. Howard, G. Macaro, R. Morrison, D. Peggie, A. Roy, L. Stevenson, and N. von Aderkas. ‘Titian after 1540: Technique and Style in his Later Works’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36, 2016, 6–39.

Plesters, Joyce. ‘Tintoretto’s Paintings in the National Gallery’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 4, 1980.

A. van Loon, L. Speleers, E. S. B. Ferreira, K. Keune and J. J. Boon. ‘The relationship between preservation and technique in paintings in the Oranjezaal’ In The object in context: crossing conservation boundaries: contributions to the Munich congress 28 August–1 September 2006. ed. D. Saunders, J. H. Townsend, and S. Woodcock, IIC, 2006. 217–223.

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names (Mineral): | Chinese: ci huang or shi huang (pinyin), tz'u huang or shih huang English: orpiment French: orpiment German: Rauschgelb, Operment Italian: orpimento Japanese: shiō, kiō, sekiō Russian: аурипигмент Spanish: oropimente |

||||||

| Synonyms (Pigment): | English: arrhenicum, arsenic trisulfide, arsenikon, auripigment, auripigmento, auripigmentum, jalde, operment, oropiment, yellow arsenic French: arsenic jaune, arsenic sulfuré jaune German: Arsenblende, Arsenikon, Auripigment, Gelbe Arsenblende Greek: Αρδενικόν Latin: arsenicum flavum, auripigmentum |

||||||

| Common Names (Synthetic): | English: king's yellow, royal yellow French: juane royal, orpin artificiel German: Königsgelb Russian: жёлый мышъяк |

||||||

| Nomenclature: |

|

||||||

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Yellow |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Yellow 39 (77085, 77086) |

| Chemical Name: | Arsenic Sulfide |

| Chemical Formula: | As2S3 |

| ASTM Lightfastness Rating | |

| Acrylic: | Not Rated |

| Oil: | Not Rated |

| Watercolor: | Not Rated |

| Properties | |

| Density: | 3.49 g/cm3 |

| Hardness (Mohs): | 1.5–2.0 |

| Refractive Index: | nα = 2.400 nβ = 2.810 nγ = 3.020 |