MY FIRST INTRODUCTION to the art of fresco was at a very young age when I was taken to the Detroit Institute of Art and exposed to the Detroit Industry Murals by Diego Rivera. I'll never forget the awe and excitement I felt as I walked through the gates to the courtyard where the murals live. I still feel it today — on every visit. It wasn't until many years later that my wife and I had the pleasure of meeting two people who worked as apprentices on these murals under Rivera, Lucienne Bloch, and Stephen Pope Dimitroff. It was through their generosity and tutorage that we embarked on a journey to become fresco artists. We have found that learning the day-to-day workings has only increased our excitement and awe for the work that has been done before us. The present article will supply a brief history on fresco and enough instruction to enable the reader to feel this same excitement.

First, in order to create a fresco, it is necessary to understand the process. In fresco buono you paint with pure pigments on wet lime plaster. As the plaster cures, a layer of crystal forms over the pigment, locking it into the surface. This is what gives fresco its beautiful matte finish and permanence.

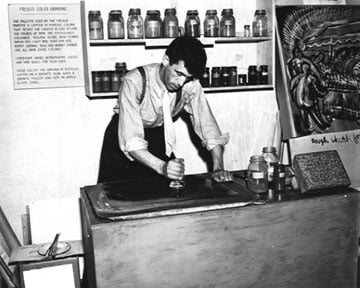

Fig 1. Mural assistant Paul Holmes Coates grinding colors for use in a fresco painting by Diego Rivera.

It is commonly believed that the paintings on the walls of the famous caves at Lascaux, France, were put there for magical or religious purposes. It is impossible for us to know what reason those early artists actually did have for the lovely, often highly realistic, renderings of animals. What is most certainly true is that they had no idea, when applying chalk and charcoal and colored earth to the damp limestone walls, that they were creating the world's earliest known frescoes. If it is correct that the images were a means of reaching a level of influence, a spiritual avenue to affecting earthly life, then they are possibly also the first icons. At some 30,000 years of age this cavernous art museum surely proves that wall-painting is the mother of all painting. Fresco has been used in Western and Eastern art for at least 4,000 years.

Although there are few wall paintings remaining, we know that the Greeks developed it — and true fresco — to a high level of expertise. Perhaps the best evidence exists within the Minoan remnants on the islands of Crete and Thera. The former is most famous, and reconstructions of the fabulous Palace of Knossos give some idea of the colorful, spontaneous, and eloquent design-sense of the Minoans. There contains evidence that fresco was not just for the privileged and royal minority; many household wall decorations are found there.

The Greek methods spread and continued through the Roman civilization. They evolved and changed; the Romans gave names to the processes and pigments, some of which we use today. For instance, sinopia is so called for the red oxide pigment traditionally used to draw it, the Roman sinoper.

Fig. 2. Architectural scene with theater mask from a Roman wall painting from the cubiculum of a villa at Boscoreale near Naples, late first century C.E., New York City, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Pompeii and Herculaneum, "fortuitously" preserved for us by layers of volcanic ash, we can see how fresco was used to brighten windowless stone rooms. The Romans painted scenes of the outdoors, lively people, and tromp loeil doors, arches, and windows to help relieve claustrophobia. Here, too, art was used for sacred purposes; gods and the rituals serving them were depicted in both an educational and decorative manner. In some houses there is found layer-upon-layer of lime plaster, indicating that wall paintings may have been changed much as we change wallpaper.

The methods of the mural painters of ancient Egypt were not true fresco. They are called fresco secco to indicate that the painting was done on dry plaster. Here various gums and glues were derived from plants to bind the pigments to the surface, as well as casein, made from milk solids. Unlike wet lime painting, most of these, except casein, are far from permanent. Some magnificent wall paintings can be blown away with the slightest breath, like so much dust.

So called after the name of one of them, coemeterium ad catacumbas, the catacombs of Rome were never actually used to hide Christians during persecution, nor were they secret places for worship. They were, however, the burial place of thousands of Christians. The wall paintings found there are simple depictions of biblical parables considered appropriate symbolically to environs of the dead: the raising of Lazarus, Jonah being regurgitated by the fish. The Christians were not the first to decorate their burial places; they were continuing a tradition in a style long practiced by the Romans. Roman painting had evolved to a level of such sophistication that the simple brushstroke was prized; the ability to depict a complete subject with a minimum of strokes is considered a very modern concept in art. To the untrained eye, and to later artists who copied the style, such art may appear awkward and clumsy. In later years, when the history of the earlier, great civilizations was lost, artists seem to have continued from a starting point of those simple, childlike images. Realism and perspective were no longer employed.

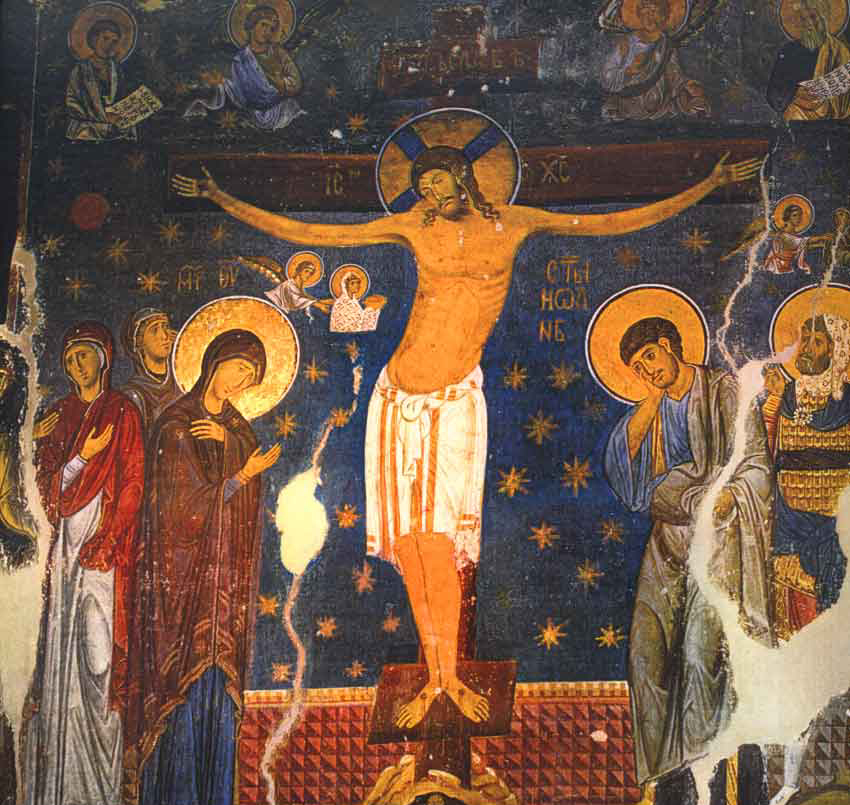

Fig. 3. Crucifixion of Christ from a fresco in the Studenica Monastery, Serbia, 1209.

The crisis of the Roman Catholic Church, and its subsequent division, helped to preserve the old ways, and, in a way, helped to preserve fresco buono. Cut off from the continuing evolution of Western Art, the Eastern Orthodox frescoes are thought to be true to the Greek and Roman methods. When Constantinople fell to the Crusaders in 1204 the painters employed by the church needed to go elsewhere for work. The artists who decorated Our Ladys Church at Studenica in Serbia are known to have come from there. The monastery shared many of the trials and tribulations endured by the people during their dramatic history, and approximately only one-fifth of the original frescoes remain. Extensive restoration work has made it possible to distinguish between the layer of the thirteenth-century frescoes and the more recent sixteenth-century layer. The sixteenth-century ones mainly repeated the subject matter, all are themes common of Byzantine churches from approximately the same period. Other frescoes in the chapel, originating a quarter of a century after those of Our Ladys Church, indicate the path Serbian painters took, unassisted by Greek painters. Contact with the Classical World was lost and Byzantine art began its own life.

The tradition of Byzantine fresco painting continued in the Balkans up to the nineteenth century. However, in Russia an evolution took place from the fifteenth century onwards when mural painting began to grow stylistically closer to icon painting. The increase in the number of figures and accessories, the refined execution, the effects of modeling and the miniaturists taste for detail all required more time and application, which made finishing secco necessary. The preferred binders were egg, wheat starch, and sturgeon [fish] glue.

In the mean time, occidental mural painting continued to be done in fresco buono as the normal procedure. Most of what was written at the time on wall painting, however, describe methods for painting on dry walls. This probably is because these were alternative methods and therefore unknown and deemed worthy of recording. Pattern books were used frequently in the Middle Ages that partially accounts for the great similarity in many of the church decorations of the time. The patterns were points of departure and medieval and Gothic artists became freer with their interpretations. A form of fresco, lime-painting, in which pigments are applied with lime on a dry or damp surface, was used extensively in the Middle Ages. The stark, cold rock walls of castles were relieved not only by the tapestries we are familiar with seeing, but also by colorful art scenes, flowers, decorative patterns. Even the outsides of castles were thus decorated; the famous Tower of London was once quite colorful.

In the later Middle Ages the Northern Gothic artists began to look to classical realism. From the thirteenth century onwards, Gothic architecture began to replace the solid wall of the Romanesque style with a diaphanous membrane containing stained glass. Translucence became a primary requirement for paintings, thereby promoting the development of a technique using glazes, as in oil painting, while the traditional techniques, especially those based on lime, produced paintings which must have appeared opaque and lacking in depth. Colognes church of St. Cecelia, c. 1300, contains wall paintings that have overlays of glazes done in fresco secco applied on top.

Italy stayed rooted in the Byzantine tradition. Frescoes and mosaics that were solemn and stylized decorated Italian churches in a style called Italo-Byzantine. Giovanni Cimabue (c. 1240–1302), in the small amount of his work to survive, seems to have been of this tradition. His notable student, Giotto di Bondone (c. 1266–1337), began to break away from it into a more naturalistic style.

Fig. 4. Mourning of Christ, fresco by Giotto di Bondone from the Capella dell Arena, Padua, c. 1307. Each angel is within its own giornata.

The Renaissance witnessed the blossoming of all the arts and fresco technique was perfected to such a high level that many of them are just as lustrous today as when they were completed. The names of the artists from that time read as a progression of style as well as technique, these are the giants of Western Art. Giotto began humanizing the subjects he painted. His Madonna is first of all a mother in an anguish of grief, and, secondly, the Mother of the Redeemer. Giottos figures are awkward and full of inaccuracies as representational drawing. But his realism is beyond anything known in his century. Massacio (1401–28) achieved the ideal representation of the human figure, drawn in harmonious, realistic proportions and convincing attitudes. In his Holy Trinity, the linear perspective is so well done the interior measurements of the chapel portrayed may be accurately computed from the information shown. The work of Fra Angelico (c. 1387–1455) harkened back to an artistic style many had left behind. But his stillness is not stiffness and his love of his subject as well as his technical prowess created frescoes of perfection. Recent cleaning reveals paintings as perfect as they were when first painted. The most famous frescoes from the time, Michelangelo Buonarrotis (1475–1564) ceiling, are not the only frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. The walls are covered with works from many artists. Raphael Sanzios (1483–1520) frescoes fill much of the Vatican Palace apartments. Included are Raphaels Bible, a series of scenes from biblical tales, as well as some surprisingly pagan-like decorative painting reminiscent of early Roman work.

It was also during the Renaissance that fresco began to decline in use. Artists wanted to have longer painting time available. The sorry state of Leonardo da Vincis (1452–1519) Last Supper is due in part to his experimenting with this; the painting was deteriorating even before he finished it. During the sixteenth century in Italy, wall painting began to include oil painting on canvas. The decline of fresco was also due to the church no longer being the sole patron of the arts. The permanence of a wall in a cathedral gave way to the wealthy merchants desire for artwork that could be transported. One reason the Renaissance produced such an abundance of art was due to the rise of a middle class. Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), the sixteenth-century biographer, was the first major collector of art who was not a monarch, nobleman, or prelate.

This is the first in a series on the "History and Technique of Fresco Painting," originally published in the Sacred Art Journal, Volume 13 Number 3, September 1992 and republished here by permission.

Glossary

arriccio

An underlying coat of plaster applied directly to the wall, consisting of one part slaked lime to two parts of sand; some fresco techniques use several layers of arriccio.

buono

Paint with dry pigments on wet lime plaster. As the plaster hardens, a layer of crystal forms over the pigment, locking it into the surface.

fresco

Italian for "fresh;" painting with dry pigments into a fresh, still wet intonaco layer of plaster. Also a term used for wall painting on dry surfaces, but more correctly called secco.

giornata

One day’s work on a fresco, usually 3–5 square meters in size.

intonaco

The last coat of plaster applied the day of painting, the intonaco (0.5–1.0 cm thick) contains less sand than the underlying arriccio layer(s). In large fresco paintings, the artist applies the intonaco plaster to complete in a short time.

pentimenti

Corrections added to the painting after the day’s work.

secco

Italian for "when dry;" painting with dry pigments in organic binders such as casein, egg, oils, or waxes.

sinopia

A stencil of the major shapes of the painting is transferred to the wall before the actual painting begins, sometimes called the cartoon. On the dried arriccio, the artist sketches the sinopia, usually first with charcoal and then with a lime-compatible pigment mixed in water. The sinopia is then traced onto paper to serve as a guide for continued work. The paper sinopia is then placed over the fresh intonaco, and the image is transferred to it in one of two ways: (1) by gently incising the lines of the drawing through the paper into the plaster or (2) by dusting dry, dark pigments through perforations in the paper along the lines of the drawing ("pouncing").