Lessons Learned from Watteau, Reynolds, Copley, Decamps, Soehnée, and Vibert

By James N. Robinson

Introduction

During the first decade of the 20th century, a startling phenomenon was witnessed in exhibitions of oil paintings throughout France:

“at retrospective exhibitions of art, many modern pictures which on their first appearance were greatly admired for their brilliance and freshness, seemed so darkened and tarnished as to be hardly recognizable.” [1]

One artist, Charles Moreau-Vauthier[2], decided to do something about it. Moreau-Vauthier had studied drawing and painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry, so he was well acquainted with the challenges of craftsmanship which beleaguered the practitioners of oil painting during the latter part of the 19th century.

Fig. 1 Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s first teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), had an early success with his painting The Cock Fight, which is an example of the Neo- Grecian style of painting popular in Europe at the time. Its masterful technique shows Gérôme’s commitment, even at 24, to extend the observance of traditional painting methods into the 19th century. Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Cock Fight, 1846, oil on canvas, 56 x 80 inches (143 x 204 cm), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Fig. 2 Moreau-Vauthier’s second teacher, Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry (1828–1886), painted The Pearl and the Wave in 1862. It is often viewed as one of French academic art’s outstanding technical and aesthetic achievements.[3] Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry, The Pearl and the Wave, 1862, oil on canvas, 32.9 x 70 inches (142.34 x 178 cm), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Charles Moreau-Vauthier exhibited at the Paris Salon between 1880 and 1887. His work honors the Naturalist movement sweeping throughout Europe in the 1880s [4], which has so often been obscured by Impressionism, which flourished during the same period.

Fig. 3 Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s recognition as a painter was somewhat limited. Consequently, his most recognizable picture, The Death of Joseph Bara[4], has suffered from rough treatment. Yet, despite its poor handling, the quality of the paint surface is in surprisingly good shape. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, The Death of Joseph Bara[5], 1880’s, oil on canvas, size unknown, Musée Municipal, Nérac

Upon attending numerous exhibitions, Moreau-Vauthier consulted with friends Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret and Alphonse-Étienne Dinet:

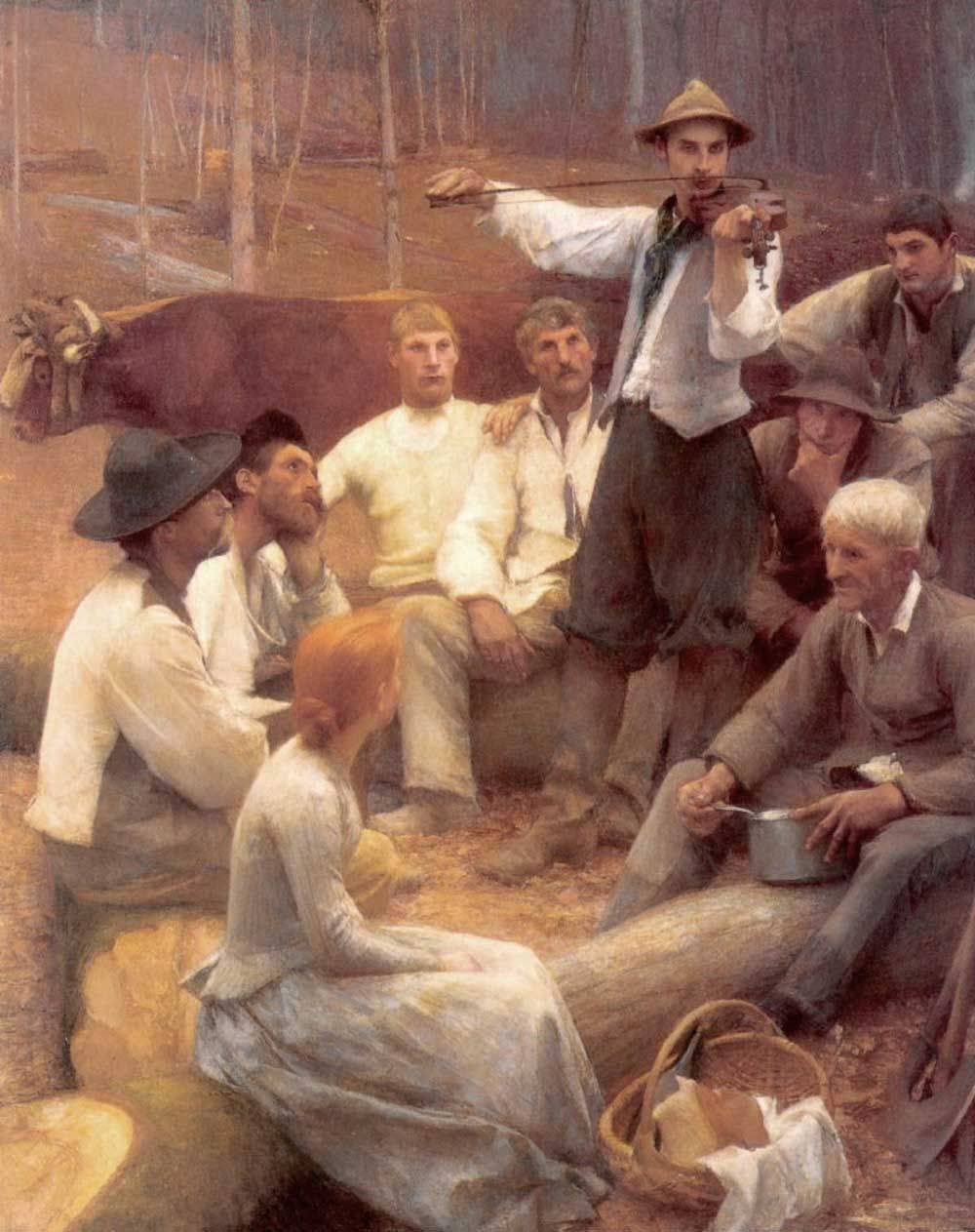

Figs. 4 and 5 I find Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s selection of artists to advise him on the technical matters of painting to be exceedingly interesting. While Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929) was a Naturalist painter who repeatedly employed a subdued palette of earth tones, Alphonse-Étienne Dinet (1861–1929) was one of the founders of the Société des Peintres Orientalistes [Society for French Orientalist Painters] and often explored the limits of Impressionist color.

Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, In the Forest, 1892, oil on canvas, 61 x 49 inches (155 x 125 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy.

Alphonse-Étienne Dinet, Slave of Love and Light of the Eyes, c. 1900, oil on canvas, 18.5 x 21.25 inches (47 x 54 cm), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

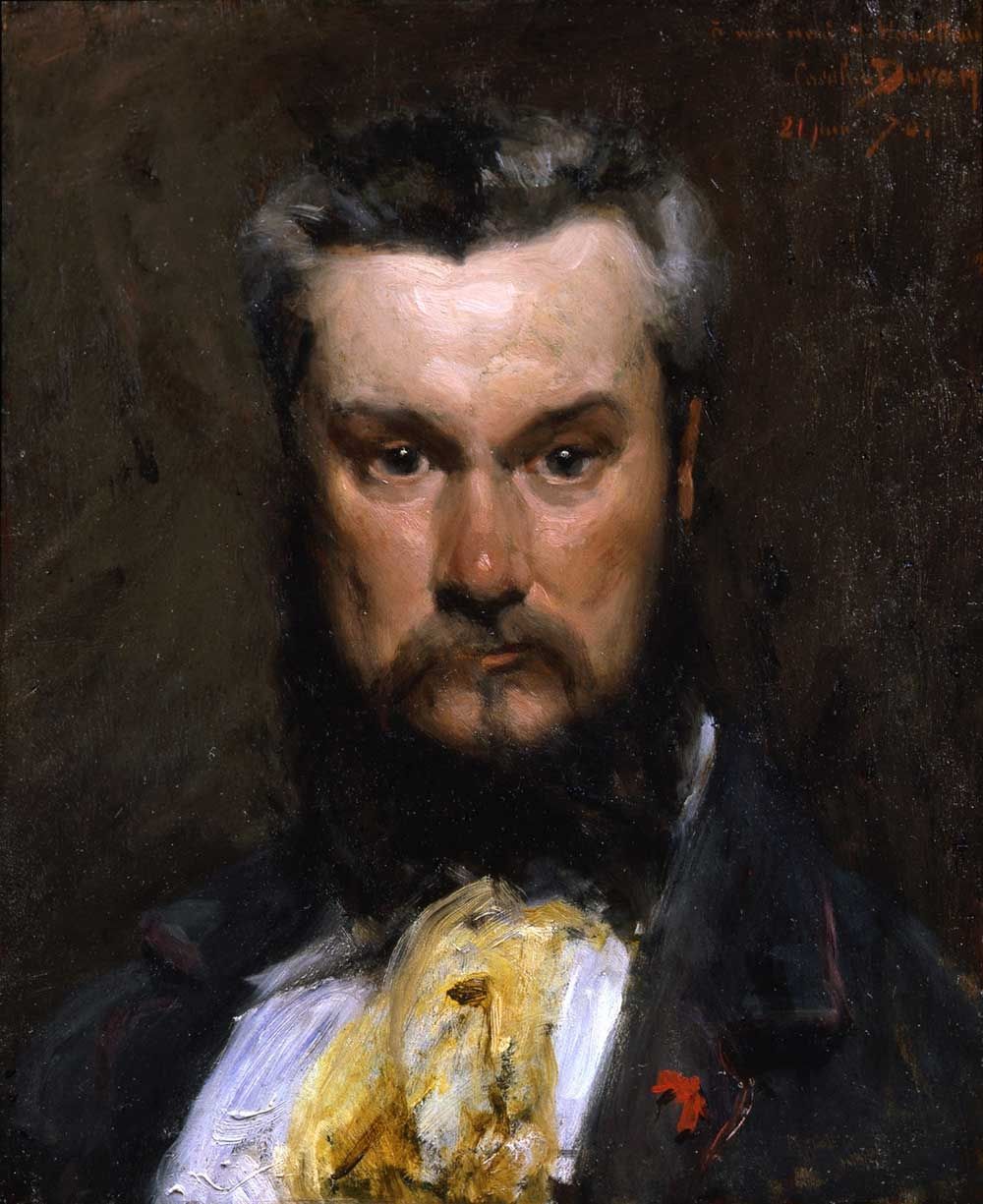

In addition, he gathered input from a noted craftsman of the era, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Carolus-Duran, and Jehan Georges Vibert:

Figs. 6 and 7 On the other hand, William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) was the most outstanding Classicist and Salon painter of his generation, with no interest in the Impressionist movement. In contrast, Carolus-Duran (1837–1917) is most notable for pioneering new methods of teaching Direct Alla Prima painting techniques to such artists as John Singer Sargent, which produced a whole new series of methodological challenges for artists and conservators.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Study of a Girl’s Head, c. 1890, oil on canvas, 17.9 x 15 inches (45.7 x 38.1 cm), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Carolus-Duran, Portrait of Hector Hanoteau, 1870, oil on panel, 23.5 x 20 inches (59.7 x 50.8 cm), Location unknown

Fig. 8 Finally, Jehan Georges Vibert (1840–1902) was an exceptional, highly regarded academic painter during France’s Third Republic. Interestingly, many of Vibert’s pictures expose hypocrisy amongst the Catholic clergy, whose influence was often opposed by numerous supporters of the Republic. This thread of anti-clericalism has not always boded well for the preservation of Vibert’s paintings; St. John Vianney College in Miami owns an extensive collection of his work, but some conservators have criticized their management of Vibert’s pictures. Jehan Georges Vibert, The Preening Peacock, date of completion unknown, oil on panel, 14.7 x 18.2 inches (37.4 x 46.3 cm), Private collection

And then, in 1912, Charles Moreau-Vauthier published The Techniques of Painting:[6]

“Comparing the rapid deterioration with the admirable preservation of canvases executed by the masters of bygone centuries, you felt, as you have told me, impelled to undertake the present study. Your book will be very helpful to artists, not only for the future—but also for the present—of their works.” [7]

Unfortunately, Moreau-Vauthier’s writings have fallen into obscurity. That is regrettable, for they thoughtfully address the challenges of oil painting and present solutions from the last great generation of French academicians before they were overshadowed by modernism. Some of their solutions have merit; others are misguided—but they all are fascinating and instructive for those working today.

One subject thoroughly explored within Moreau-Vauthier’s book is the sinking-in of colors and how to counteract that problem by oiling out or applying retouching varnish.

Oiling Out—Today’s Preferred Method

The simple process of oiling out is often touted as a safe alternative to applying retouch varnish in areas of dried oil paint films that have sunken in.

And the process is safe and straightforward. Arthur Pilans Laurie summarizes the procedure in Step 9 of his book, Simple Rules for Painting in Oils:

Oiling out will result in darkening. If the picture has become matte in some places, try polishing it with a lint-free cloth. If oiling out must be resorted to, use the very minimum of oil, rubbing off all excess with a rag.

Yet, in the same book, Laurie wisely states: “The difficulty in laying down rules for painting today is that no two painters paint alike.”

Herein lies the dilemma—oiling out is a process based on artistic intent, and many artists are by nature reactive rather than proactive when it comes to charting a painting’s development.

In this five-part series of articles on sinking-in, oiling out, and retouching varnishes, I will first review historical abuses of each process made during the late 17th through 19th centuries.

In Part 2, I’ll examine why those abuses happened.

Next, in Part 3, I’ll follow those abuse trends up to the present day.

Then, in Part 4, I’ll compare traditional texts which describe different methods of oiling out and the retouch varnishing of pictures.

Finally, in Part 5, I will cross-reference those texts and pair them with artistic intent to determine the best solution for each painting situation.

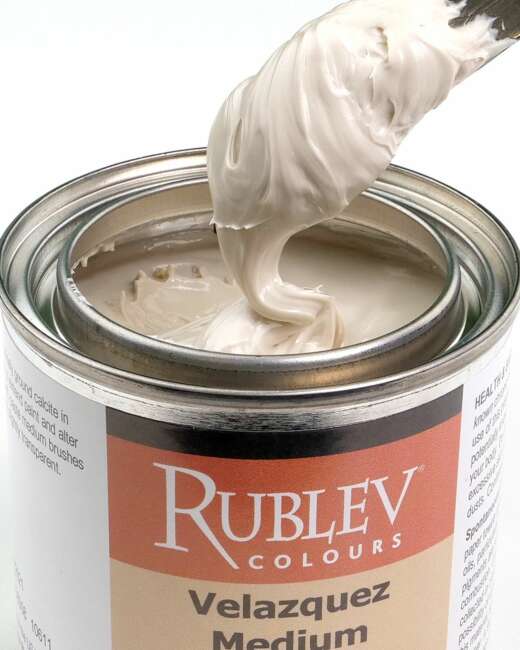

A list of Natural Pigments’ products will also be included in Part 5 to help facilitate the various applications I have discussed.

By doing this, I hope that you possess a more thorough understanding of these basic yet often misused practices and thus ensure the longevity of your paintings.

Let’s begin with a bit of art history...

Watteau’s Reactive Painting Procedures

From Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting, we learn of the unstable oil painting methods of Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). Moreau-Vauthier writes:

Watteau studied the Rubenses in the Louvre with profound attention. Monsieur de Caylus tells us this in a study in which he, unfortunately, dwells upon Watteau’s bad habits rather than good ones. He accuses him of having sometimes used oil to excess and losing something of his magnificent technique in the process. He liked to paint rapidly, and “to accelerate his effect and his execution,” he painted “greasily.”

“It was his habit,” says Caylus, “when he worked over a picture, to rub it all over with oil, and to paint into this. This momentary advantage injured his pictures very considerably in the long run, and the injury was still further increased by a certain uncleanliness of habit which must have affected his colours. He very rarely cleaned his palette, and often went for days without re-setting it. His pot of oil, which he used so freely, was full of dirt and dust, and mixed with all sorts of colours which came out of the brushes he dipped in it.”

Mariette also says: “He was not very particular in the matter of cleanliness, and this, added to his abuse of oil, has done a great deal of harm to his pictures. Nearly all of them have suffered. They have lost the tone they had when they left his hands.”

Gersaint, who also knew him personally, deplores his abuse of oil and adds: “It must be admitted that some of his pictures are perishing in consequence day by day, that they have changed colour completely, or have become very dirty, and that nothing can be done to mend matters; but, on the other hand, those which are free from this defect are admirable, and will always hold their own in the finest collections.” [8]

Fig. 9 Many of Watteau’s paintings suffer from the abuse of excessive oiling out. Jean-Antoine Watteau, Fete Champetre, 1722, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

These eyewitness accounts of Watteau’s methods address the challenges of oiling out in the minds of many artists. For them, the process is not strictly a solution to bring out a sunken-in area of dried paint. Instead, it is often seen as a preparation before adding a new layer of paint to a work in progress. In their excellent book, American Painters on Technique: The Colonial Period to 1860, conservators Lance Mayer and Gay Myers record the trend:

The process of “oiling out”—applying a thin layer of oil to dried paint before beginning a new painting session—had been typical since the eighteenth century. However, some artists criticized the practice because the oil could turn dark and yellow.[9]

Watteau, who died in 1721, seems to have been one of the pioneers and abusers of this manner of preparation.

Reynolds’ Misguided Experiments

By the end of the 18th century, problems related to the indiscriminate use of oils, mediums, and the process of oiling out had increased. This was exacerbated by the painting practices of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). Moreau-Vauthier summarizes the downward spiral:

The decadence was drawing near; soon, an era of absolute disorder was to set in. No tradition was to survive. The painting was to become a hotch-potch without system, without delicacy, without forethought, which was doomed to perish within a few years. Before this gaping tomb, one master, Reynolds, recoiled, drew back, offered his homage and worship to the admirable artists of the past, and pronounced the funeral oration of traditional painting. He was strangely absorbed in processes. Gifted with the analytical and critical spirit of decadent periods, he studied methods with the utmost ardor. He even went so far as to destroy pictures to discover how they were painted. But it would seem that the secrets he sought to penetrate were inviolable or that their solution lay outside the scope of his inquires, for his studies resulted in paintings that evaporated, turned yellow, cracked, and perished even during his lifetime. Surprised and greatly troubled at first, he ended by declaring philosophically: that the best painting is that which is liable to crack. This philosophy, too frequently adopted after him, served but to aggravate the evil to come. Reynolds further inaugurated a very artistic but over-prompt and impulsive manner, which often led to fragility and evanescence despite its artistic beauty.[10]

Fig. 10 Regardless of their exquisiteness, numerous pictures of Sir Joshua Reynolds reflect his misinterpretation of traditional paint applications. Joshua Reynolds, Lady Frances, Countess of Lincoln, 1781–1782, oil on canvas, 24.4 x 18.5 inches (47 x 1.8 cm), The Wallace Collection, London

Oiling Out and the Rise of Retouching Varnish In Portraiture

By the 1760s, the mistreatment of oiling out had grown substantially. Portrait painters especially praised the process of melding transitions of flesh tones from one sitting to the next. John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) liked to wipe his dried underlayers with “a little Oyl” as a preparation. Many of his American portraits have yellowed as a result.[11]

Fig. 11 The green transitions of the flesh tones and the yellowing of the Reverends’ white clerical collar and preaching bands suggest the overabundant use of oils and varnishes in Copley’s portrait. John Singleton Copley, Reverend Joseph Sewall, c. 1766, oil on canvas, 30 by 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm)

Artists of note, including Benjamin West (1738–1820), the second president of the Royal Academy in London, and Thomas Sully (1783–1872), the British-born American portrait painter, were even oiling out as a final varnish.[12] In addition, it was recommended as a cure for bloom, cloudiness that sometimes tarnished paintings coated with mastic varnish.[13]

To make matters worse, oiling out was no longer confined to using linseed, poppy, or walnut oils. Megilps, thixotropic gels made from cooked mixtures of oil, lead, and mastic spirit varnish, were also being applied as early as 1767,[14] as were heat-bodied oils.

Retouching varnishes were used as well. Benjamin West concocted a substance containing spermaceti (a waxy substance found in the head cavities of sperm whales), combined with mastic varnish and poppy oil, which he added freely to paintings for retouching in the 1770s; and in 1778, a formula for Benjamin West’s Spirit Varnish, comprised of sandarac varnish dissolved in alcohol and mixed with fir balsam, was published and promoted as another alternative for the process.[15]

This trend toward exotic mediums and varnishes would continue throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

1824–Year of the Tin Tube

Today, portrait painter John Goffe Rand (1801–1873) is credited with the invention of the paint tube, but that is not entirely true. While he did patent the design in 1841, Moreau-Vauthier places the date 17 years earlier:

In about 1824, an Englishman proposed using tin tubes to preserve colours which, like lake and Prussian blue, deteriorate in bladders. The invention was rewarded with a silver medal and a premium of ten guineas from the Society of Arts in London.[16]

In his 1830 book, De la Peinture à l'huile, Jean-François-Léonor Mérimée wrote of the invention, too. Yet, regardless of the date, the availability of tubed paint further distanced artists from their historic craft:

Artists gave themselves up to the liberty of handling with thoughtless enthusiasm. In some cases, this amounted almost to a frenzy. [Alexandre-Gabriel] Decamps obtained an impasto which was a kind of crust. “It is rocky, masonic, crinkly, scratched, rubbed, fretted, floating in bituminous glazes, full of accidents, and yet grandiose and passionate in spite of all this alchemy of the laboratory, the evils of which will become more and more pronounced with time.” [17]

Figs. 12 and 13 These Singeries mock widespread views in France during the 1830s, which favored the belief among connoisseurs and many painters that the old masters should dictate aesthetics. However, Decamps’ paintings, in such poor condition, could just as well lampoon his ignorance of mediums and their use.

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, The Experts, 1837, oil on canvas, 18.25 x 25.25 inches (46.4 x 64.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, The Monkey Painter, 1833, oil on canvas, 12.6 x 15.7 inches (32 x 40 cm), Louvre Museum, Paris

Artists as Manufacturers

One of the results of the period’s alchemical temperament, yet general ignorance, is that it encouraged some artists to manufacture their blends to counteract the sinking-in of pictures. The two most influential painters doing this were Charles-Frédéric Soehnée (1879–1878) and Jehan Georges Vibert (1840–1902).

Soehnée published a technical treatise in 1822, which posited a peculiar theory concerning Jan van Eyck (1390–1441), who, with his brother Hubert, is often considered the founder of oil painting. Soehnée speculated that van Eyck painted his pictures with a mixture of encaustic and varnish. As ridiculous as this sounds today, Soehnée’s opinion gained traction, and his reputation grew, so by 1829, he co-founded the company Soehnée Frères. A retouch varnish he produced was based on a thin shellac/alcohol solution and became extremely popular in Europe, England, and America.

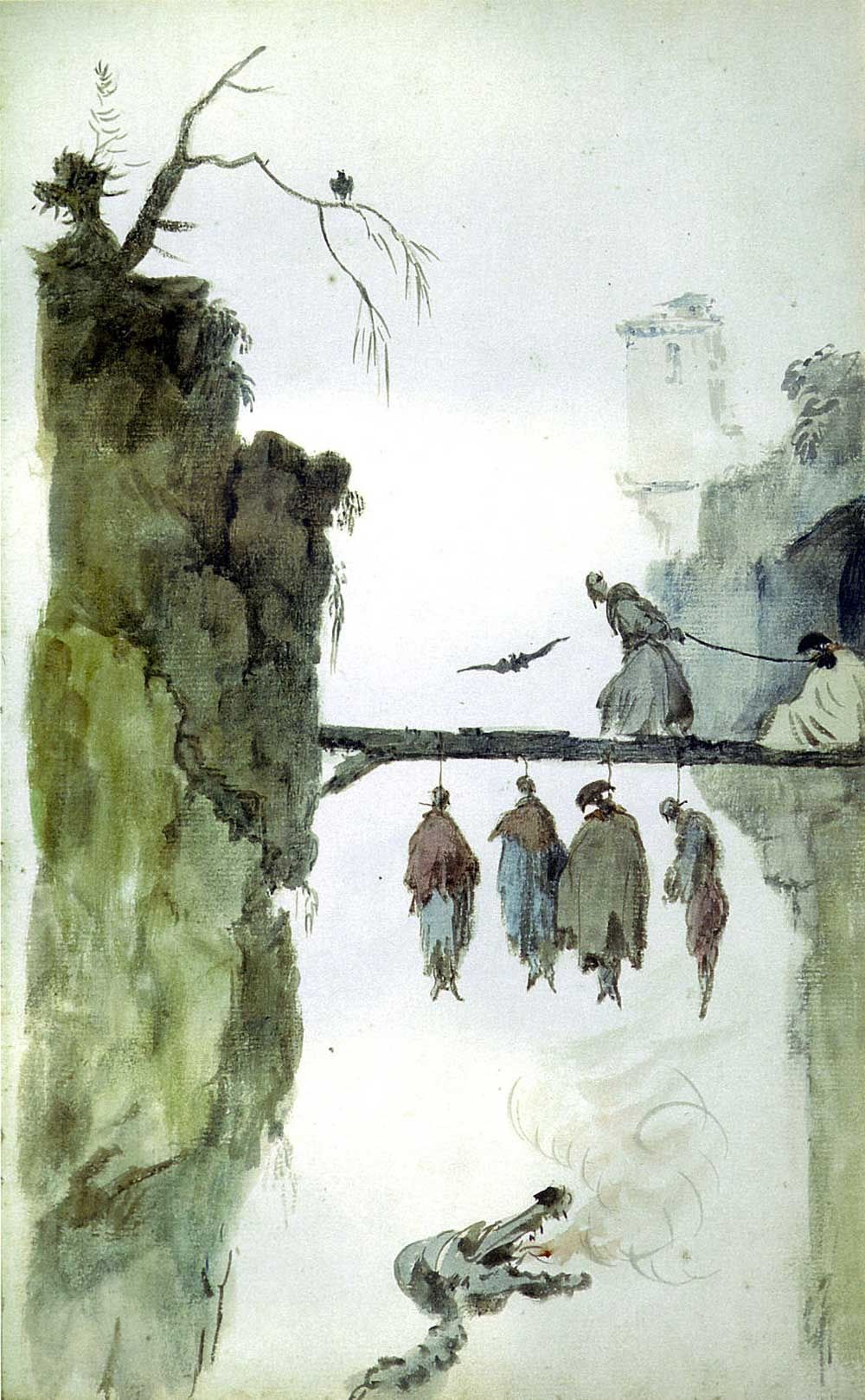

Figs. 14 and 15 As an artist, Soehnée is best known for a series of 100+ drawings, watercolors, and lithographs of Grotesques, executed in 1812. Vibert, as we have previously noted, was a superb academic painter of historical, genre, and religious scenes.

Charles-Frédéric Soehnée, Etudes (3), 1817–1819, watercolor

Jehan Georges Vibert, The Serenade, 1877, oil on panel, 14.76 x 18.11 inches (37.5 x 46 cm), Private Collection

Jehan Georges Vibert disputed the efficacy of Soehnée’s solution. In La Science de la Peinture, published in 1891, he condemned its popularity:

Alcohol varnishes are not used in oil painting, but there is one of them which is too frequently made use of on account of its being convenient; viz.—Soehnée retouching varnish. It does not mix with colours and is only used to get out an embu. [Author’s Note: Embu is equivalent to the English word sinking. It means a part of the picture where the painting is dull owing to the foundation having absorbed the oil.] This varnish is absolutely pernicious because it has a basis of gum lac [shellac], and being altogether insoluble in oil, the coatings of colour are thus separated into isolated flakes, making the picture a mass of leaves without adhesion. Essence varnishes have all one significant drawback: they do not evaporate entirely but leave a viscous and coloured residue besides the resins with which those varnishes are made...[18]

Vibert believed that the best resin to incorporate into an oil medium was not a hard resin, such as copal or amber, because a hard resin could only be dissolved with heat in an oil bath. Instead, he recommended a normal resin: “…uncoloured... crystallisable, perfectly transparent, soluble in cold oil and petroleum.” [19]

Dull patches or sinking, which we shall later talk about painting a picture, should not trouble the artist since he can remove them with a light scumbling of retouching varnish whenever they appear.

As this varnish dries in a few minutes, it can be immediately painted over; and as it forms a solid link between the different coats of paint, it is even vital never to repaint any piece without first painting it over with this varnish as a preliminary.

It can be mixed with colours to make rapid glazings, but it is too volatile to be used for solid painting. For this purpose, painting varnish should be used.[20]

This unnamed miracle standard resin, with which Vibert composed his popular retouching varnish, is thought to be none other than dammar combined with a petroleum solvent.[21]

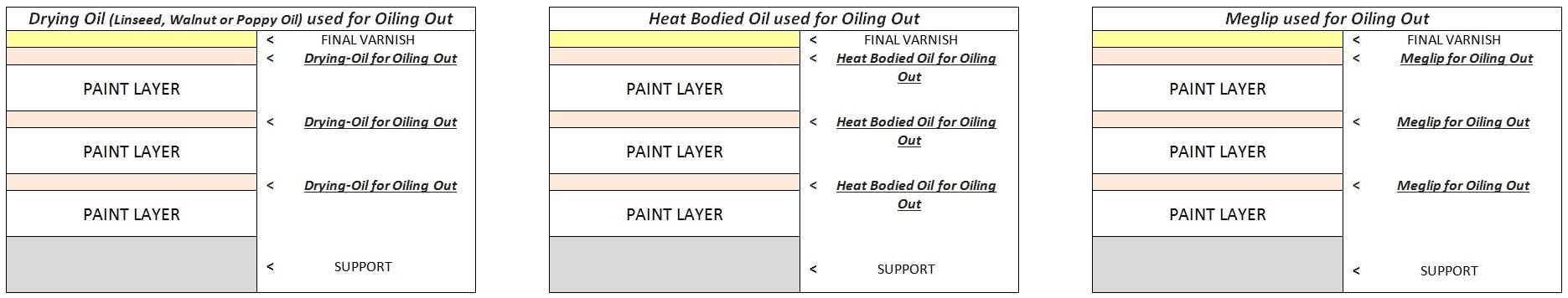

The Paint Structures Revealed

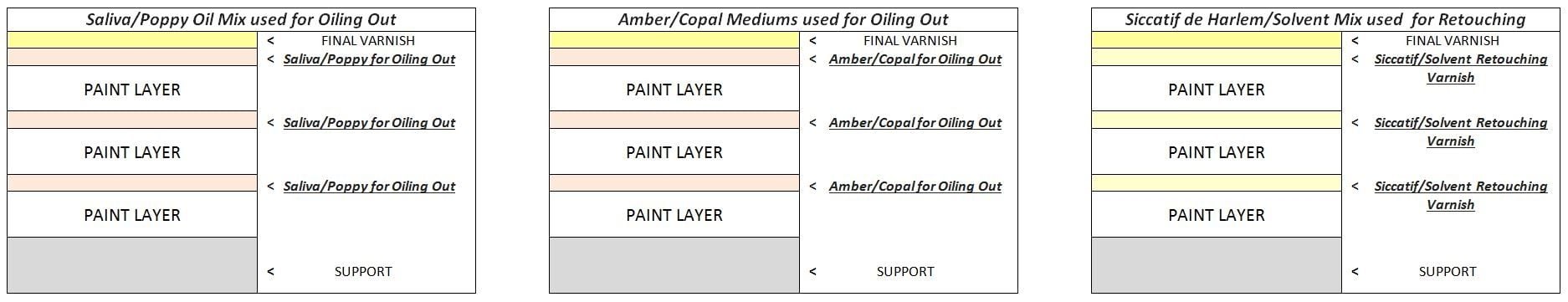

So far, we’ve learned quite a bit about mixtures for oiling out and retouching employed during the late 17th through 19th centuries. The diagrams below will help you visualize how these products were interlaced within the structure of the period’s paintings.

The first series shows a representative sequence for oiling out. Three layers are charted, as many artists at the time strove to finish a painting in three stages. The diagrams also assume that a layer of oil was used as a temporary varnish, so works could be displayed soon after they were completed without showing signs of sinking in. Lastly, a final varnish is recorded as being applied after the recommended one-year waiting period:

Fig. 16 Cross-section diagram of oiling out and retouching employed during the late 17th through 19th centuries

What is the result of this layering?

Yellowing and darkening of a picture due to excessive use of oil; that oil cannot be removed by a conservator because it has dried as an integral part of the paint film. As Frederic Taubes warns: “Yellowing due to storage of a painting in darkness can be improved by exposure for a period of several weeks to a strong light or a mild reflected sunlight. However, if yellowing and darkening of a painting have occurred as a result of improper technique or faulty materials, the discoloration of the painting cannot be remedied.” [22]

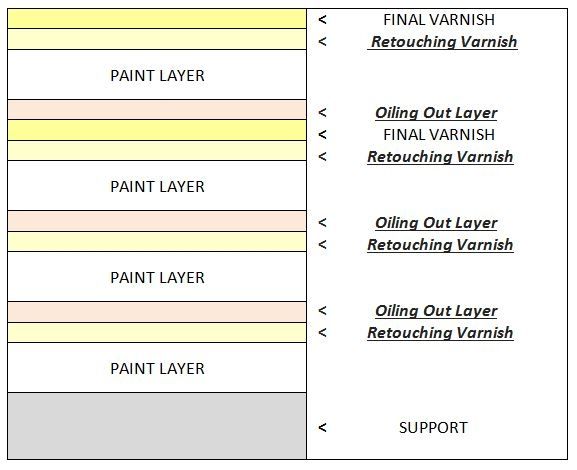

Here are two more diagrams for oiling out, which I’ve covered. In the first, the process is also utilized as a final varnish, while in the second, it is added as a remedy for the bloom:

Fig. 17 Cross-section diagram of oiling out as a final varnish and to correct bloom

What is the result of these layerings?

In the first instance, there is no final sacrificial varnish[23] used to protect the painting from environmental conditions, so the finished work is very susceptible to injury.

In the second example, extra oil has been applied to cure bloom—which it does not. The bloom will return, and the picture will become yellow and darken.

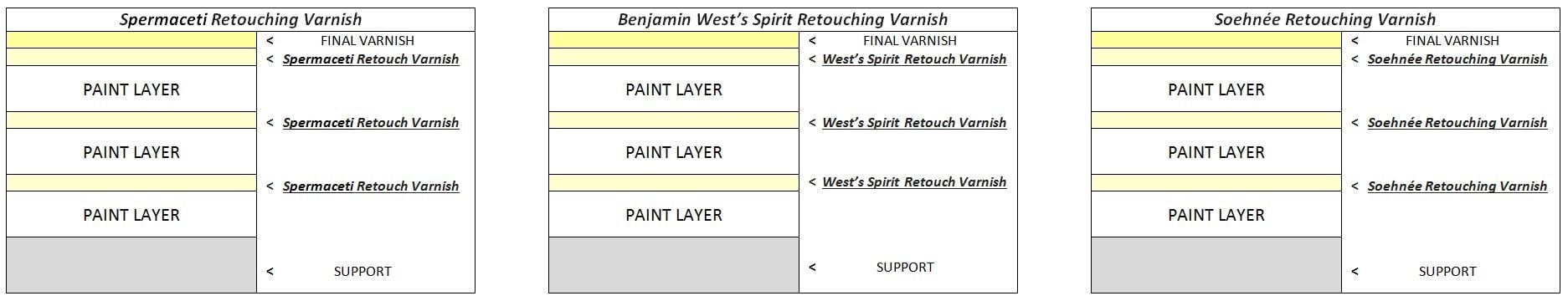

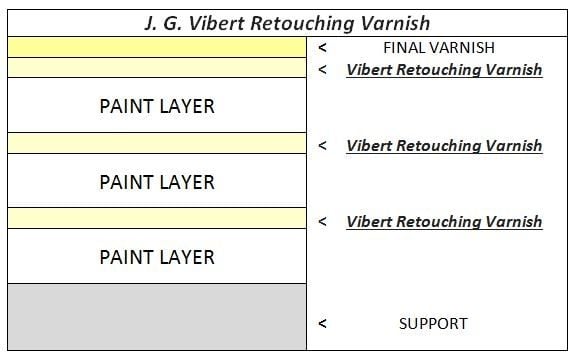

Here are examples of the construction of paintings using the retouching varnishes mentioned earlier:

Fig. 18 Construction of paint layers using retouching varnish

What is the result of these layerings? Yellowing, darkening, and increased brittleness.

But these are not the only flaws introduced between the paint layers. In a series of email exchanges that I’ve had with George O’Hanlon, he clarified the point:

“Yes, retouching varnish is damaging, but more because it increases the susceptibility of the paint layer to solvents used during restoration. Secondarily it increases the brittleness of the layer.”

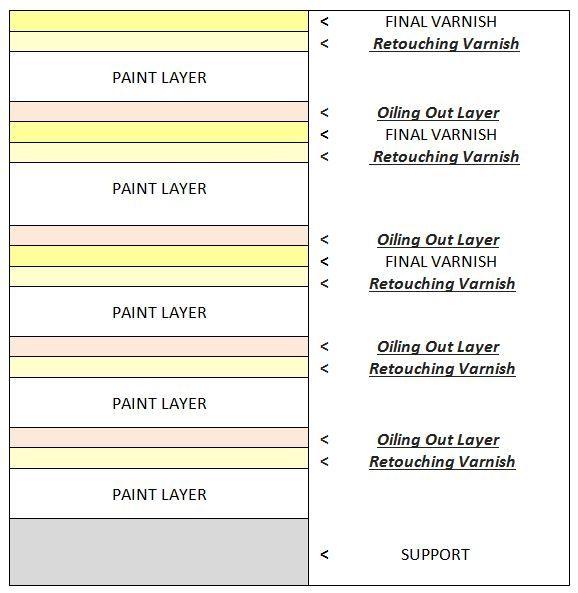

However, let’s not forget that there were many other combinations made famous during the centuries I’ve been discussing: “...we will merely add that some painters prefer a simple mixture of saliva with poppy-oil (made on the palette) to rub the dry place they have occasion to repaint.” [24] Amber mediums had also become highly fashionable by the middle of the 19th century, as did copal.

Siccatif de Haarlem, a blend of copal resin and spike, was used to lay in paintings, used as the medium for color application; and used as a retouch varnish between paint layers.[25] Siccatif de Haarlem dried quickly, supposedly through evaporation, and therefore was believed to have no adverse effects on the paint mixed in with it.[26]

Or was it made from thickened oil and dammar varnish, as Max Doerner suggested?[27]

Or, as Kurt Wehlte declared, from dammar varnish and turpentine?[28]

As manufacturers did not always label the contents of their merchandise, artists themselves didn’t know the composition of the mediums they purchased. So, now we have these additional diagrams:

Fig. 19 Construction of paint layers using complex mediums

When, too, was a painting ever finished? The subject was a hotly disputed topic in the second half of the 19th century. Many artists applied a coat of final varnish to their work, only to let it dry and paint over it again:

Fig. 20 Painting over final picture varnishes

And what about those conscientious painters who thought they were following the advice of reliable sources, who sometimes encouraged them to apply a preparation of oil over retouching or final varnishes before they began each painting session? So, now we have a diagram that looks like this:

Fig. 21 Oiling out over retouching varnishes

And some repeated the offense over and over and over…

So now we get this:

Fig. 22 Complex paint construction with oiling out, retouching varnish, and final picture varnish layers

This configuration can only be described as disastrous. How will a conservator ever care for such an imperfect array of fragile layers successfully?

In truth, these charts display just a few of the countless products used for oiling out and retouching during the period I’ve covered. With unusual drying oils (grandi), varnishes (spar), solvents (kerosene), resins (succinum), waxes (castor), and driers (Japan) joining the ranks of additives to mediums, the variations had become infinite. Even beer and water were being flaunted as worthy components.[29]

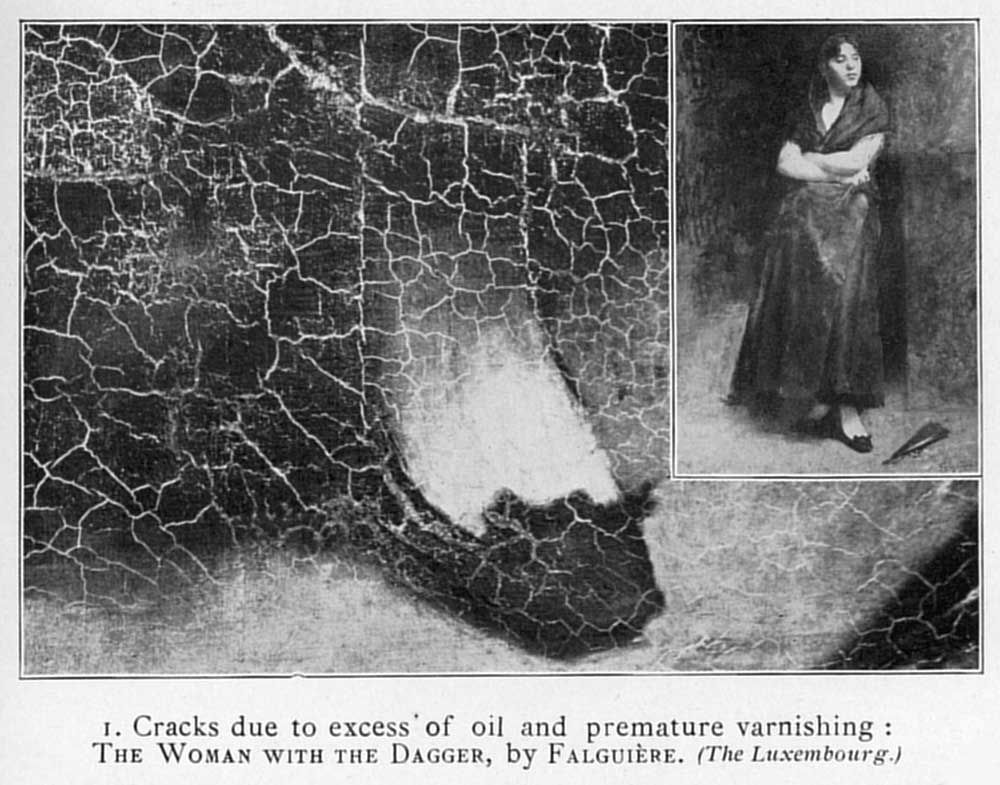

I’ll end Part 1 of this article with a visual representation of what a painting subjected to this layering looks like. Charles Moreau-Vauthier describes the pattern:

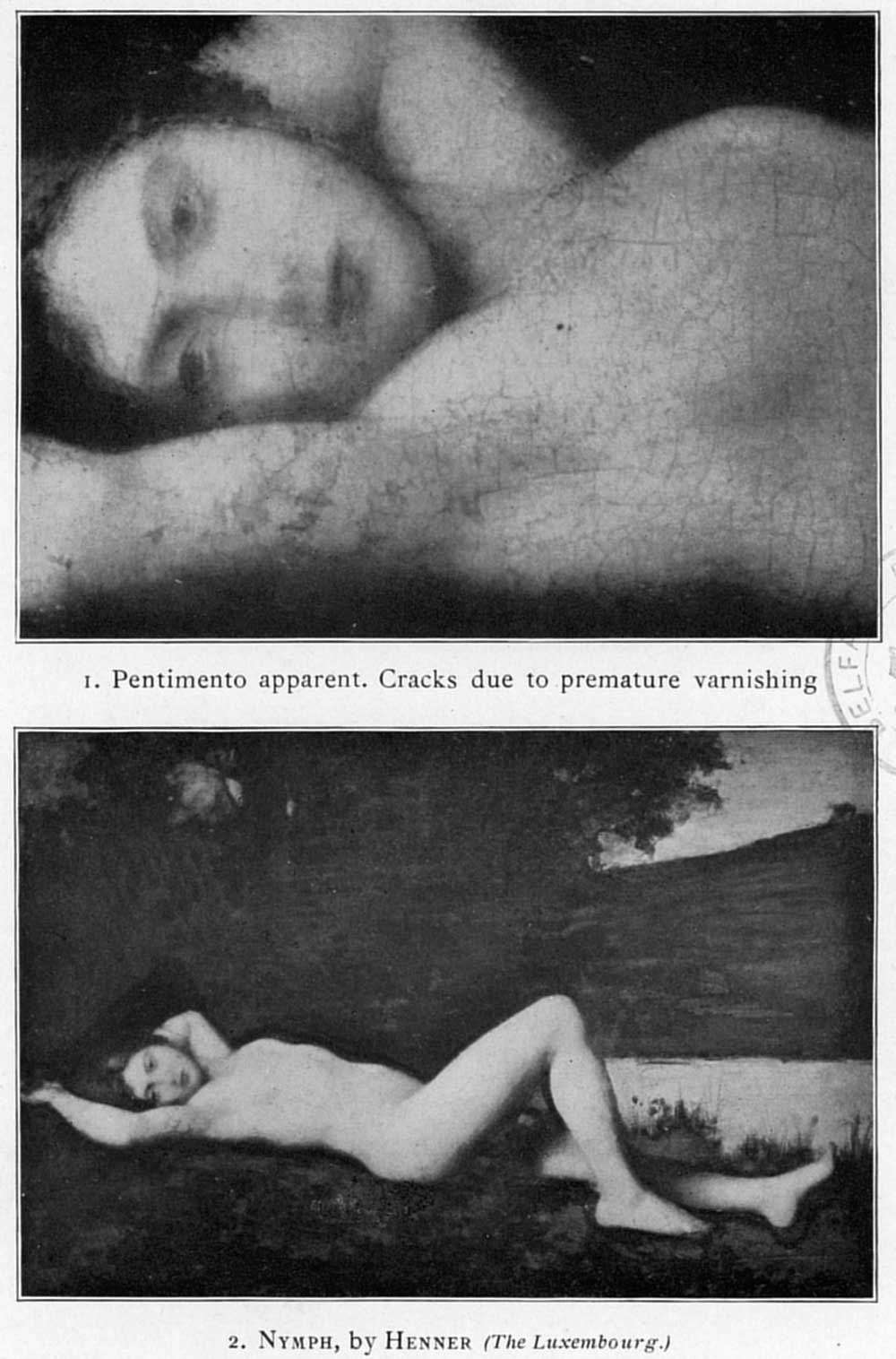

Sometimes oil and varnish combine to commit misdeeds of a different kind. The varnish cracks and separates into regular flakes, detached from each other. This betrays the presence of too much oil in the impasto and the premature varnishing of the picture. (We shall see that varnishing should be postponed for a considerable time.) A very characteristic example of this kind of injury is to be seen in a picture by Falguiere in Luxembourg of a woman holding a dagger:[30, 31]

Fig. 23 This image follows page 122 of Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912.

In the next installment of this paper, I’ll examine why all these abuses happened.

Notes and References

1. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: preface, page v. This statement is made by Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s friend, painter Alphonse-Étienne Dinet.

2. Charles Moreau-Vauthier (1857–1924) came from a long line of artists. His grandfather, Jean-Louis Moreau, was a tablet maker who worked in ivory. His father, Augustin Jean Moreau-Vauthier (1831–1893), was a sculptor who focused on allegorical figures, historical busts, decorations, and ivory. Charles’ brother, Paul Moreau-Vauthier (1871–1936), was a sculptor too and achieved great renown throughout France for his monuments and memorials.

![Augustin Jean Moreau-Vauthier [Father], A Florentine Lady, c. 1892, ivory, gilt on silver, pearls, onyx, 17.9 inches](https://www.naturalpigments.com/media/wysiwyg/blog/OilingOut1/Vauthier_Florentine_Lady.jpg)

Fig. 24 Augustin Jean Moreau-Vauthier [Father], A Florentine Lady, c. 1892, ivory, gilt on silver, pearls, onyx, 17.9 inches (45.7 cm), Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Fig. 25 Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s brother Paul sculpted La Parisienne, which crowned the Porte Binet of the Exposition Universelle of 1900.

Fig. 26 Paul Moreau-Vauthier’s Boucicaut Monument of 1914 pays tribute to Aristide Boucicaut, who, with his wife Marguerite Guérin, created Le Bon Marché, the first modern department store. Upon her death, Marguerite outlived her husband and generously bequeathed her fortune to the Bureau of Public Assistance and Hospitals of Paris.

3. On page 202 of his book, Old Masters and New: Essays in Art Criticism, published in 1905, artist, writer, classical theorist, and teacher Kenyon Cox (1856–1919) described Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry’s The Pearl and the Wave as: “the most perfect painting of the nude done in the last century One notes the infinite suavity of subtle line, the absolute but unostentatious science of the drawing, the nacreous loveliness of the colour, the solid yet mysterious modeling, almost without light and shade, the perfection of the delicate surface. These things make a pure masterpiece.”

4. In Art of the Actual: Naturalism and Style in the Early Third Republic France—1880–1900, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), Richard Thomson, Watson Gordon Professor of Fine Art at the University of Edinburgh, writes on page 1: “Naturalism was the dominant aesthetic of late nineteenth-century France. In painting as in literature it set the cultural tone, shaped and suited the mentalité of the mainstream, and worked hand-in-hand with the political ideology of the Third Republic.” On page 9, Richard Thomson continues: “Take an example of an art historian writing about 1880 on a famous old master, [historian] Henri Havard praised [Rembrandt’s] The Night Watch, ‘above all for that exactitude, that truth in the physiognomies and in the action which one identifies as naturalism.’ Exactitude was understood as a virtue, overlapping with scientific accuracy (precise evidence, pure knowledge) and moral truth (honesty, clear thinking, bons sens). Such values could easily become ideological, as will be seen, in a republican mentalité which strove to assert its values of modernity and rationality.”

Fig. 27 Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch, 1642, oil on canvas, 142.9 x 172 inches (363 x 437 cm), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

5. The death of Joseph Bara was a popular theme in French art during the last decade of the 18th century and throughout the 19th century, beginning with an unfinished picture painted by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825):

Fig. 28 Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Bara, 1794, oil on canvas, 46.8 x 61.4 inches (119 x 156 cm), Musée Calvet, Avignon

Bara was especially favored as a subject during the early 1880s, as the Third Republic worked to define its political, moral, and economic initiatives throughout France. For example, artist Jean-Joseph Weerts (1846–1927) painted two images of Joseph Bara between 1880 and 1883, earning him the coveted Légion d'honneur in 1884. One was a historical portrait:

Fig. 29 Jean-Joseph Weerts, Joseph Bara (1780–1793), 1882, oil on canvas, Musée d'Art et d'Industrie, Roubaix

The other was a history painting. On page 34 of Art of the Actual, Richard Thomson tells of the influence of Weerts’ efforts: “Jean-Joseph Weerts’ painting The Death of Joseph Bara represents the death in 1793 during the Vendée Wars of a teenage drummer who, as he was killed by a counter-revolutionary Breton Chouans, yelled out ‘Vive la République!’ Although this was a historical scene, Weerts pulled out all the naturalistic stops—freezing the scene at the instant of Bara’s last cry, throwing the figures in from the canvas edges to give a powerful sense of impulsive violence, detailing expressions, costumes and weapons—to maximize the sense of actuality. Commissioned by the state in 1880 and a success at the Salon of 1883, the painting was first hung in the Elysée palace, where its theme of republican devotion would have been evident to all the President’s visitors. In addition, 500,000 photographs were printed for distribution to schools throughout France, so that Bara’s dutiful martyrdom could stand, via the arresting Naturalism of Weert’s picture, as an example to millions of schoolchildren.” Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s painting of the same subject seems to capitalize on the popularity of the Bara theme.

Fig. 30 Jean-Joseph Weerts, Death of Joseph Bara, 1880, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

6. I chose Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting, published in French and English in 1912, as a primary reference because too often modern historians and technical bulletins dismiss books such as these as outdated. While Moreau-Vauthier’s text obviously lacks the latest conservation/restoration knowledge and makes occasional historical errors, that is greatly outweighed by the insight gained from this skilled artist who, through the quality of his own commentary and those of his artist friends and colleagues, shares insight into the painting practices of the period. I balance the observations of this book with the scientific assessments in Lance Mayer and Gay Myers’ American Painters on Technique books, and other more recent technical publications on painting.

7. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: preface, page v—vi. In the Preface to The Technique of Painting, artist Alphonse-Étienne Dinet is full of admiration for Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s attempt to right the many wrongs endangering the legacy of French painting.

8. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: pp. 38–39.

9. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: The Colonial Period to 1860. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2011: p. 164. The history of oiling out has deeper roots than the eighteenth century. Some scholars believe that it developed as a Venetian Renaissance process, and specifically cite Veronese as a practitioner.

10. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: pp. 44–45.

11. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: The Colonial Period to 1860. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2011: p. 30.

12. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: The Colonial Period to 1860. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2011: p. 164.

14. There are accounts that amber varnish and balsams were also used as additives to mediums at this time.

15. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: The Colonial Period to 1860. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2011: p. 31.

16. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: p. 51. The Translator’s Note to Moreau-Vauthier’s book states that the author does make occasional errors concerning dates, but counters that such “historical inaccuracies in no wise affect the practical value of Mons. Moreau-Vauthier’s vivacious treatise.”

18. Vibert, Jehan Georges. The Science of Painting. London: Percy Young, 1892. (First Published in 1948 by The Dial Press, New York.), p. 88.

21. On pages 135-136 of The Technique of Painting, Charles Moreau-Vauthier critiques Vibert’s retouching varnish: “A petroleum varnish invented by Vibert is much used in studios, but it is not known what resin is dissolved in it. ...Many artists use these varnishes and are well satisfied with them. I have, nevertheless, heard Bouguereau complain of them. It must be said, however, that he had only tried them once, to re-touch a picture already finished. ‘It had cracked’; but it is hardly fair to lay the blame on the varnish, which was applied to substances in no way prepared to receive it. The best of remedies may do harm if used in unfavorable conditions. [Joseph] Bail also told me that he was by no means pleased with Vibert varnish.”

22. Taubes, Frederic. Painting Materials & Techniques. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1968: pp. 116–117.

23. A final varnish is a sacrificial layer, meaning that it is not intended to stay on forever. It is meant to be removed every 20 to 30 years and be replaced with a new layer of varnish to protect the painting. Paintings without a final varnish on them are very susceptible to environmental damage. However, a final varnish may also break down and discolor over time. Thus the final varnish on a painting should be removed and renewed every quarter century or so.

24. An (anonymous) American Artist. Handbook of Oil Painting: Being chiefly a condensed compilation from the celebrated manual of Bouvier, with additional matter selected from the labors of Merimee, de Montabert and other distinguished continental writers in the art. New York: John Wiley & Son, 1872: pp. 141: n.

25. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: 1860–1945. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2013: p. 59.

27. Doerner, Max. The Materials of the Artist and their Use in Painting. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1962: p. 108. Doerner considers Siccatif de Haarlem as “when pure, unharmful.” Siccatif de Courtai he deems “oversaturated with lead and manganese, which has already ruined many pictures.”

28. Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. American Painters on Technique: 1860–1945. Los Angeles: J. Paul. Getty Museum, 2013: p. 114: n373. 21.

30. Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912: p. 125.

31. The cracks are distinct from other craquelure which can appear in an oil painting. Charles Moreau-Vauthier describes those patterns on pages 124 and 125 of his book, too: “The cracking of a priming, as we have already noted, entails various disasters. …The brittle preparation—a defect from which many works of the Flemish Primitives have suffered—is betrayed by regular cracks, in the shape of minute squares very close together, a kind of coat of mail which appears even upon such solidly painted pictures as those of the Van Eycks (see the Virgin with a Donor in the Louvre). This network of cracks comes from the size in the priming.”

Fig. 31 Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and Child with Chancellor Rolin, c. 1435–1441, oil on panel, 26 x 24.4 inches (66 x 62 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris

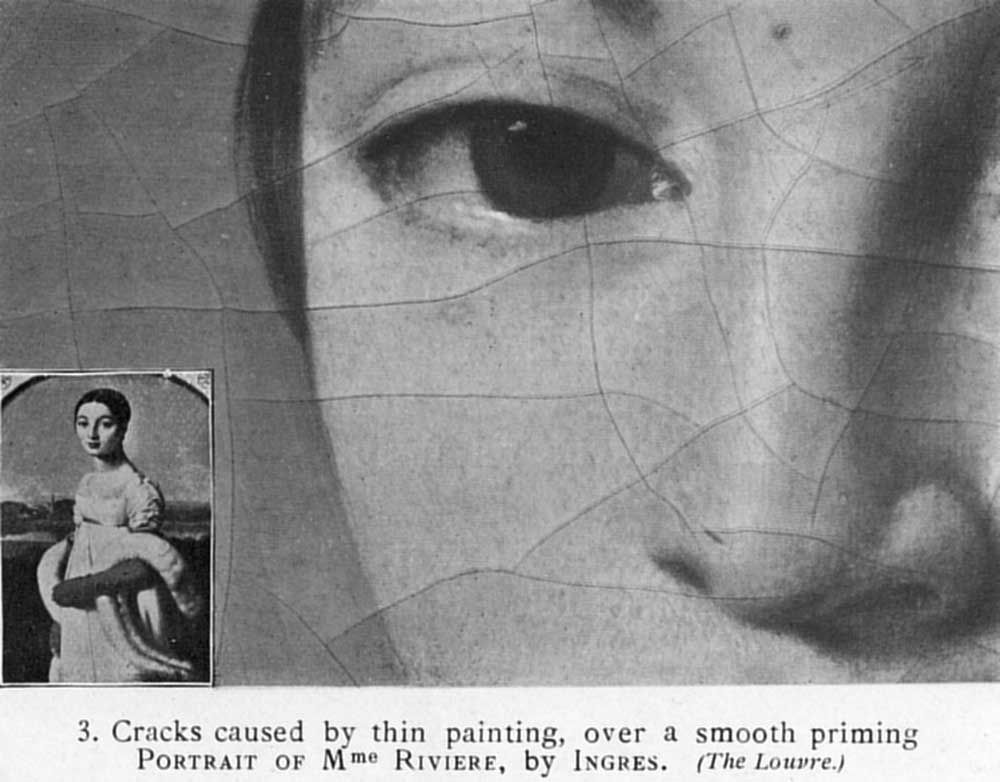

“We have seen what dangers threaten canvases which have received a very thick priming in over-smooth layers. The over-thickness induces large, round spiral cracks, such as may be seen in the portrait of a young girl by Ingres, in the Louvre:

Fig. 32 This image follows page 126 of Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912.

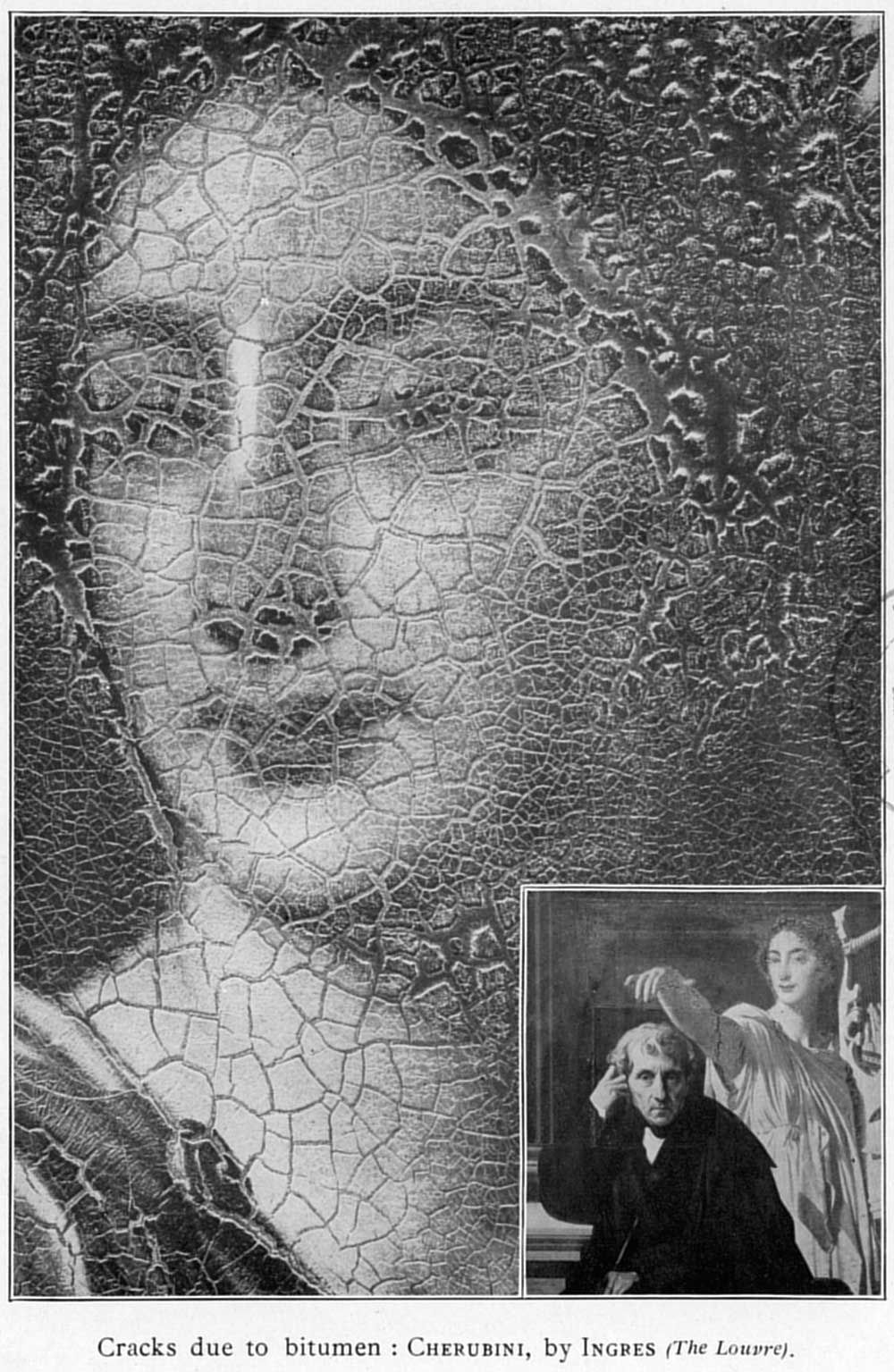

“When a coat of dark colour is laid upon a light one not properly dry, the differences in the drying processes of the two cause a play of opposing forces, producing gaping cracks and rents which lay bare the under-painting. In a picture painted with colours too freely mixed with oil, cracks of the same kind will appear, forming tiny lakes or islands with indented edges:

Fig. 33 This image follows page 124 of Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912.

“When the prematurely applied varnish alone is in fault, it, too, produces cracks in squares, which expose the paint, and leave it open to a very dangerous enemy, damp. This makes its way between the flakes of varnish and gradually attacks the painting below:”

Fig. 34 This image follows page 128 of Charles Moreau-Vauthier’s The Technique of Painting. London: William Heinemann, 1912.

© 2018 James Robinson

Special thanks to Natural Pigments for publishing this work.

Thanks also to a dear friend and artist Stuart Loughridge, Kitsch painters Luke Hillestad and Jeremy Caniglia, and illustrator extraordinaire Scott Gustafson for proofreading this article. I couldn’t have tied it all together without the input and love of my partner, Sarah Howard.

If you have questions about this article, please contact me at [email protected], or call me at 651-699-1573.

About the Author

James N. Robinson studied drawing and painting under Richard Lack, the founder of the Classical Realism movement. Upon graduation, he taught in The Atelier’s full-time program for five years and was a contributor to the Classical Realism Quarterly journal. In 1993 he founded The Art Academy in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was the first atelier-style school in America whose primary focus was teaching children and teens traditional art methods.

Concordantly with the founding of his school, James Robinson began exhaustive research into historic painting practices with the intent to revive those procedures and aid modern representational artists in creating archival work.

Today, James divides his time between mentoring children and teens in time-honored drawing and painting processes, teaching classes and workshops to adults on historical drawing and painting methods, and lecturing on essential painters of Western Art. Their aesthetics and procedural theories enrich artists’ lives.

Workshops* and Lectures

Current Workshop offerings include:

- Van Eyck: Methods and Mediums

- Venetian Painting: Methods and Mediums

- Caravaggio: Methods and Mediums

- Verdaccio Underpainting

- Bistre Underpainting

- Grisaille Underpainting

- Direct Painting

- The Painting Methods of Harold Speed

- The Painting Methods of Solomon J. Solomon

- Historic Figure Drawing Methods

Current Lecture topics include:

- Jan van Eyck

- Caravaggio

- Vermeer

- The Art Collection of Guillermo del Toro

*All workshops use Natural Pigments paints, mediums, supports, and supplies.

If you want more information on workshops or lectures, please get in touch with James N. Robinson at [email protected], or call him at 651-699-1573.

Additional Reading

Please read Simple Rules for Painting in Oils for additional information on this subject.